Introduction

I am not a strong chess player - it’s always seemed to me more like study than play. However, I do like the ideas in chess: a ragtag army of pieces with different moves, battling to protect their king. I wondered if I could take those ideas that many players are already familiar with, and mix them together with some newer game mechanics from the last 500 years of board game design. This collection contains chess games I’ve designed with hidden information, bluffing, deduction, role selection, and yes, zombies. It also contains my favourite chess games by other designers that add a twist to the classic. They can all be played with a standard chess set and common items like pencil and paper, coins, and playing cards. For a more deluxe experience, I offer custom chess cards and player screens.

Hopefully, serious chess players can enjoy these games as a light break between regular chess games, and new chess players can use them as a gentler introduction to the classic game. Players of different chess abilities that might find a game of regular chess frustrating may enjoy exploring these games together.

Table of Contents

- Zombie Chess is a game where you bury each piece you capture under one of your pieces. If you move off a buried piece, it comes back from the dead as a zombie. (2 players, chess set, coins, pencils, and paper)

- Masquerade Chess is a combination of chess and deduction games like Mastermind. Pieces move regularly, except when they capture. Start the game by choosing which capture moves each of your opponent’s pieces will use, then try to deduce how each of your pieces can capture. (2 players, chess set, pencils, and paper)

- Telepathic Chess asks you to predict what your partner will do. (4 players, chess set, deck of cards, and a coin or checker)

- Two Move Chess makes both players simultaneously choose two pieces to move each turn, but choosing the same piece cancels out. (2 players, chess set, and deck of cards)

- Adrenaline Chess adds power ups to chess. (2 players, chess set, and checkers set)

- Tar Pit Chess uses cards and checkers to trap your opponent in tar. (2 players, chess set, checkers set, and deck of cards)

- Chess Golf makes players race to plan the best route, as the pieces caddy each other around the board. (1 or more players, chess set, deck of cards, timer, coins, pencil and paper)

- Crowded House is the only four-player game I know of on a standard chess set. (4 players and chess set)

- Cooperative Chess lets you play together against the game. (2 players, chess set, and deck of cards)

- Half Alice Chess moves pieces through the looking glass to a parallel universe after each move. (2 players, chess set, and checkers set)

- Chess960 is a game designed by Bobby Fischer to mix up the game opening by randomly choosing your starting position. (2 players, chess set, and deck of cards)

- Synchronous Chess makes both players write down a move, then move at the same time. (2 players, chess set, paper and pencil)

- Appendix A shows how to turn a standard deck of cards into chess cards.

Zombie Chess

Just because you’ve captured a piece doesn’t mean you can stop worrying about it. In Zombie Chess, it can come back from the dead and shamble across the board until you destroy it permanently.

Setup

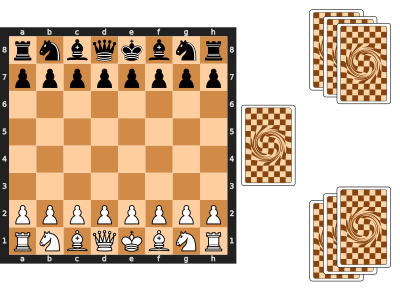

Set up the chess board normally, and gather a few coins. Four is usually enough. Each player will also need paper and pencil to draw an 8x8 grid to record where you secretly bury your opponent’s pieces. Make it big enough to write a single letter on each square. You can also draw a second grid, if you want to track where your own pieces might be buried. The grids will be empty at the start of the game.

Place the coins on one side of the board to mark the graveyard of zombie pieces. The other side is the dust bin for destroyed pieces.

Play

All the normal rules of Chess apply, until you capture a piece. In addition to moving the captured piece to the graveyard of zombie pieces beside the board, you have to secretly bury it under one of your pieces. Choose one of your pieces, then find its matching square on your paper grid. Write the first letter of the buried piece there, or N for kNight. Don’t let your opponent see where you buried the piece.

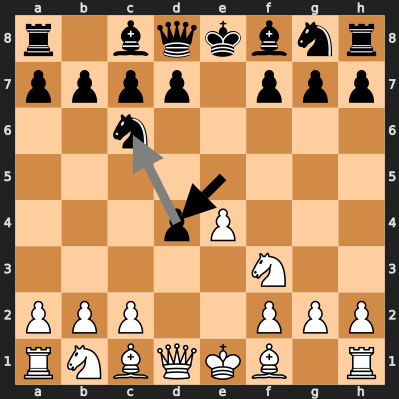

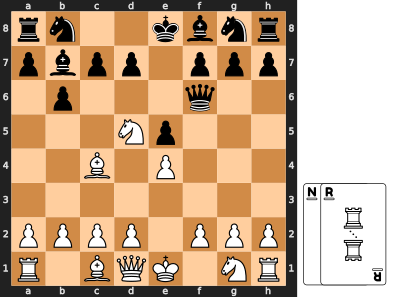

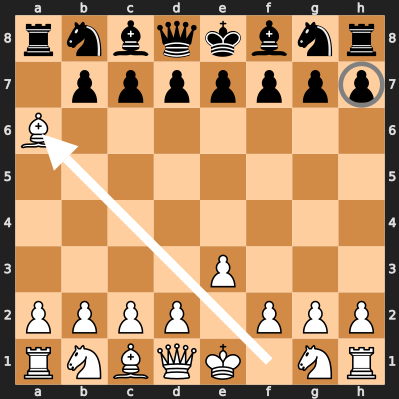

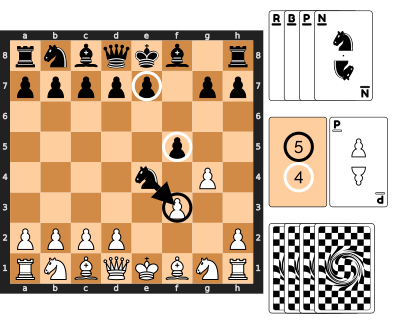

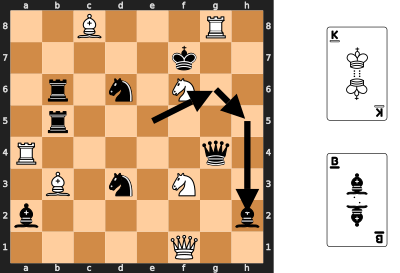

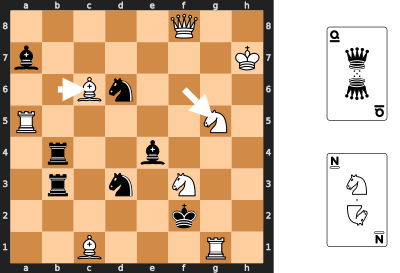

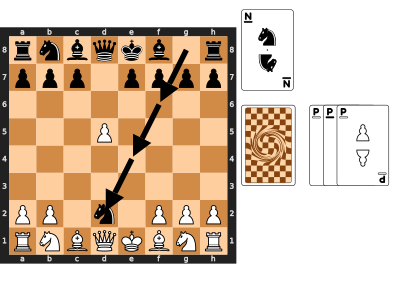

In this example game, Black has just captured a pawn at d4 and buried it under the knight at c6.

At the end of your turn, check to see whether there was a piece buried under the piece you moved. If not, say “no zombie” and say the coordinate you checked. If there is a piece buried there, bring it back from the zombie graveyard to the square on the board where it was buried. Place a coin under it to mark it as a zombie, and erase it from your grid.

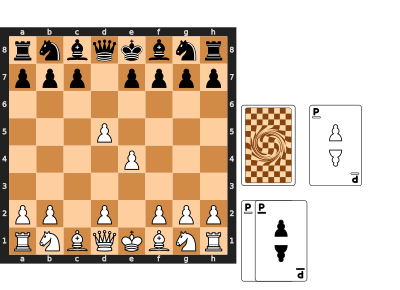

The next turn in the example game, White uses the knight at f3 to capture the pawn at d4. First, they check for zombies. There are no black pieces in the graveyard, so they say “no zombies anywhere”. Then, they choose where to bury the pawn. They decide to bury it under the pawn at b2, so they write a P in their hidden grid at b2.

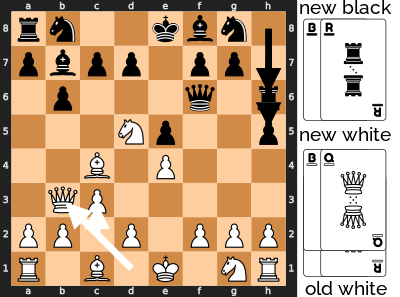

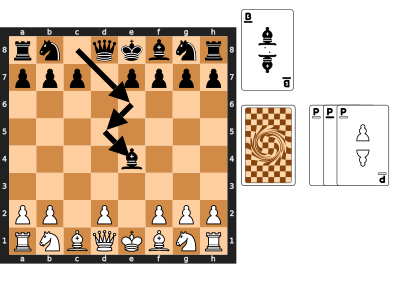

Black responds by capturing the knight at d4 with their knight at c6. First, they check for zombies. There is a white pawn in the graveyard, so they check their secret grid for the square they just left: c6. They see the P there, so they put the white pawn back on the board with a coin under it and erase it from the grid. Then they decide to bury the knight under the pawn at g7 and write an N in that square in their hidden grid.

Also at the end of your turn, check if you have any zombie pieces that you didn’t move. If so, they are permanently destroyed, and moved to the dust bin side of the board.

If you have more than one zombie piece on the board, they form a zombie horde. You can move all of them on one turn, although each piece can only move once per turn. Any that you don’t move will be destroyed at the end of your turn.

You probably don’t want to bury pawns on your back rank, because they can immediately be promoted when they come back and then moved on that turn. As with regular chess, you can promote to extra queens. Either use a queen from another set, or just keep track of which pawns have been promoted.

You can’t bury more than one of your opponent’s zombie pieces under one of your pieces. However, you can leave that piece buried if your opponent captures your piece on top of it. When they move off the space, first ask them if they revealed one of your buried pieces. If so, it comes back, and you don’t yet have to reveal the piece you have buried there.

In the very unlikely event that you capture a piece and already have a piece buried under each of your pieces, move it directly to the dust bin and say, “I cannot bury this piece.”

Game End

As usual, the goal is to checkmate your opponent’s king. If moving a piece would put your king in check by revealing a zombie, you may not move that piece. When castling, complete the move before revealing any zombies.

Masquerade Chess

Masquerade Chess is regular chess, but all the pieces above pawns have a secret identity. They use their standard moves, except when capturing. Each player knows the capture moves of their opponent’s pieces, but not their own. Who can deduce their way to victory first?

Setup

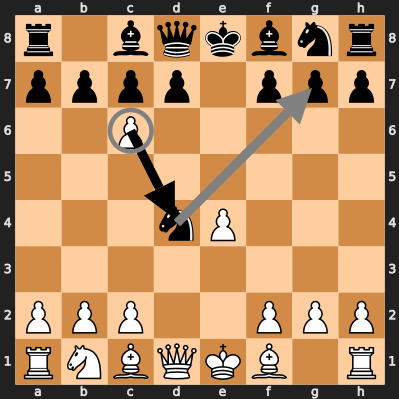

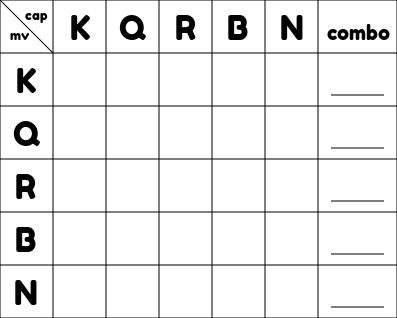

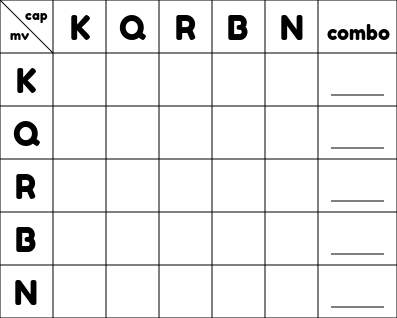

Players each draw two copies of this table:

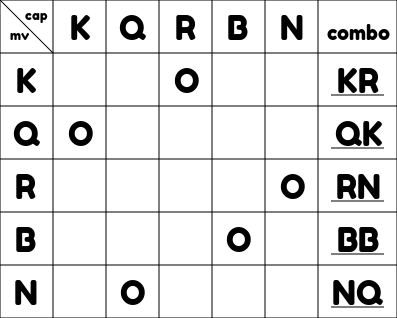

They write their opponent’s name above one table and their own name above the other. They then fill in the table for their opponent’s pieces without letting their opponent see. Circle one square in each row and column to record which of their opponent’s pieces captures using which moves. Each row must have one circle and each column must have one circle. A piece may be given its normal capture or the capture from a different piece.

Players will fill in the other copy as they learn about their own pieces.

The combo column can be helpful to fill in with the move and capture letters together, so players don’t have to keep looking at the rows and columns of the rest of the table.

Here’s an example set up where Bob has filled in the table for Alice’s pieces and left his own blank.

Alice

Bob

Play

On each turn, the player may either make a standard move without capturing, or attempt a capture. To attempt a capture, point to the piece you want to move, then to the piece you want to capture, and ask your opponent, “Capture?” If your opponent says the move is legal, perform the capture as normal. If not, you don’t move anything, and your turn is over. Either way, record what you learned in your table by writing X’s for combinations that you know are impossible and O’s for combinations that you know are correct. Remember that pawns always capture with their standard capture moves.

Game End

The game ends when one of the players captures the other’s king. Because players don’t always know their pieces’ abilities, they don’t have to call “Check”, and a threatened king doesn’t have to evade capture. The king may choose to bluff by staying where it is or even move into an attacked square. A king may castle out of check. There is no stalemate between kings: one king can capture another to win the game.

Strategy

A key part of strategy is which capture moves to assign to which pieces. It seems like it would be a big advantage to give your opponent two queens, so perhaps the queen capture should always be assigned to the king or the queen. It seems like giving it to the king makes it harder to use, because a long range capture will likely leave the king exposed. However, a king with a queen capture can defend itself very effectively.

The Queen can quickly get into position to attack, so it’s probably wise to give it a less powerful attack like the knight or king. However, even these can be surprisingly effective.

When assigning capture moves to the bishop, knight, and rook, look at which pawns they can defend. If you can make one of the pawns undefended and then try to attack it with a knight, that can be a quick, safe way to learn about some of your pieces.

As an example, KQ, QN, RB, NR, BK seems nicely balanced, and leaves the rook pawns undefended. However, assigning the same moves every game would be too predictable.

Another part of strategy is the effective use of bluffing. Keep track of what your opponent knows about their own capture moves, and put your pieces in danger if the risk is worth learning something valuable or attacking the king. Try to learn faster than your opponent and strike before they know enough to defend themselves. Move fast and break things!

History

This game was inspired by Robert Abbott’s Confusion, which Kerry Handscomb and I originally adapted as Minor Confusion by creating a more balanced set of moves and playing with a chess set. That was playable but uninspiring, so I abandoned it for 15 years. Masquerade Chess returns to the standard Chess moves, and players only learn about their pieces during capture, which slows the pace of the game.

Telepathic Chess

I like the idea of two players working together and trying to predict what their partner will do. You can decide how much talking to allow. Definitely none before your move, but it can be more fun to discuss what you thought your partner would do after they move and before your opponents move. Just don’t explain a move by talking about future moves it sets up.

Equipment

- a standard chess set

- a deck of chess cards (See how to turn standard playing cards into chess cards in appendix A.)

- a coin or checker

Setup

Shuffle together the two queen cards and two king cards, then deal them to the four players to choose colours and partners. The players with the queen cards will predict first, and the players with the king cards will move first.

Give each team a set of seven cards: pawn, knight, bishop, rook, queen, king, and checker. The predictor for each team should take the cards in their hand, and play the pawn card face up on their side of the board.

Set up the chess pieces in the standard start position. Both members of the white team sit on the side of the board with the white pieces, opposite both members of the black team. Place the coin or checker beside the board, as a trophy, halfway between the two teams.

Play

Players take turns being the mover and the predictor, handing the cards back and forth to keep track of who will play a prediction card next turn.

On your team’s turn, the predictor will play a card face down, next to the face-up card. The piece cards predict that their partner will play the matching piece, and the checker card is like a copy of the face-up card. (Think of C for checker and C for copy.)

Then the mover makes any legal chess move.

The predictor flips the face-down card to show what they predicted. If the mover moved a piece type to match the card that was face down, pull the trophy towards your side of the board. If they moved a piece type to match the card that was face up, do nothing. If they didn’t match either piece type, push the trophy away.

The trophy can be in three positions: beside the middle of the board, the white side, or the black side. If you have to push or pull it beyond those positions, the losing team has to remove one of their pieces, and then place the trophy back in the middle position. For example, if it was beside the white side of the board and the black mover didn’t match either card, the black team would have to remove one of their pieces from the board. After removing a piece, put the trophy back beside the middle of the board.

After moving a piece and resolving the prediction, the mover takes the hand of cards and picks up one of the cards from the table. If one of them is a checker card, pick it up. Otherwise, pick up the card that started the turn face up.

Losing Eight Pieces

When you lose pieces through capture or missed predictions, place them beside the board, along one side. When you have lost eight pieces, one next to each square of the board, stop leaving a prediction card face up on the table. From that point on, your team only plays one prediction card face down.

Winning the Game

Capture the opponent’s king to win the game. Because a piece is sometimes removed after the regular move, it may be possible to capture a king when they weren’t in check. You should still say “check,” when a piece is threatening the king.

Tactics

Forcing king moves is usually good in regular chess, but here it makes your opponents’ prediction much easier. Playing to a slightly weaker position that has three good responses can be better than the stronger position with one obvious response. You might sometimes want to predict incorrectly to remove a piece that frees up a stronger piece, like a rook. If your opponents predict correctly, you may have to remove a piece before your turn. That can let you remove a pawn and immediately attack with a piece that it was blocking.

Two Move Chess

Players simultaneously choose two piece types to move, then move their chosen pieces from least to most valuable. It was inspired by Richard Vickery’s Nibelungenlied.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a deck of chess cards. (See how to turn standard playing cards into chess cards in appendix A.)

Goal

Capture your opponent’s king. There’s no check or checkmate, because the cards and simultaneous choices mean that a piece threatening the king might not be allowed to make the capture.

Setup

One player takes a pawn of each colour and hides one in each hand. The other player picks a hand and then plays that colour. Don’t worry, though, the simultaneous play means that White has less advantage.

From the deck of cards, use one card of each piece type. Exclude the pawns, so you should end up with 10 cards: 5 of each colour.

Put the rest of the cards away, you won’t need them. Separate the cards by colour, and give the five black cards and 16 black pieces to the Black player and the white cards and pieces to the White player. Place the chess pieces in the standard starting position.

Finally, White picks two cards and places them face up in front of them. For your first game, pick king and rook.

Play

Each turn has two phases, played by both players at the same time: choose cards, then move pieces from least to most valuable.

Both players secretly choose two cards and play them face down. One player will start with two cards face up, and cannot choose those. Once all four cards are played, reveal them.

Now players use their cards to move pieces, ordering the cards from least to most valuable: knight, then bishop, then rook, then queen, then king. Cards can be used to move either a piece of matching type, or one of the player’s least valuable pieces (usually a pawn). If all of a player’s pawns are captured or blocked, they could use any card to move a knight or whatever their least valuable, movable piece is. If cards are used to move a different type of piece, they are still played in the order of the cards.

If both players chose the same two cards, then both cards are eliminated and no pieces move. If each player chose one matching card and one different card, then the matching card is eliminated and the other card makes two moves. When one card makes two moves, the two moves may be with the same piece or different pieces, even with different piece types, so long as each move matches the rules described above. Whether you’re using one card or two, you may not move the same pawn twice in one turn.

If you play a card, and it’s not eliminated by matching your opponent’s card, you must make a move with that piece type or with your least valuable, movable piece type. For example, if you play a rook card, have no rooks left, but do have at least one pawn that can move, you must move a pawn.

Once all the moves are finished, the player with four cards face up puts them all back in their hand. The other player leaves the two cards face up.

Rare cases

Chess pieces move as in normal chess. If you only remember the basic rules, you can probably skip this section and come back to it if you have questions.

As in regular chess, pawns can move two squares from their starting square. Castling is allowed with a king card, if neither the king nor the rook have moved and the squares between them are empty.

If you’re not familiar with the details of chess rules, just ignore this paragraph. When you castle, it doesn’t matter if an opponent’s piece is threatening the king’s square or any of the squares it will move through. Pawns do not capture en passant, but they do promote when they reach the back rank.

Example

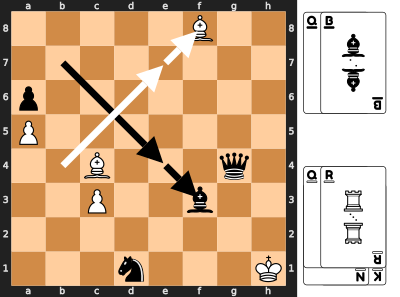

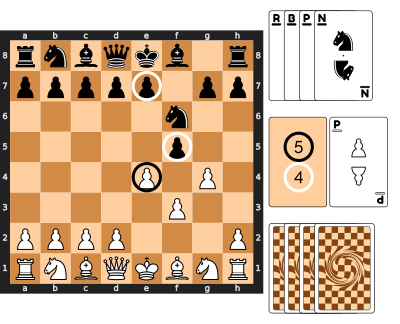

Here’s an example turn, starting with White’s old knight and rook cards left on the table from the previous turn:

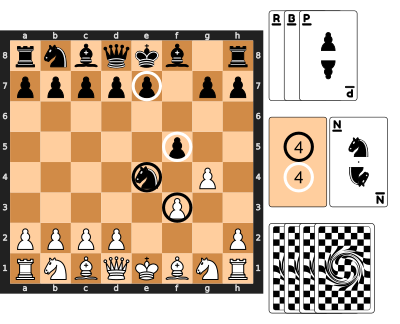

Black is threatening to capture the king with two queen moves, so White should probably play a queen card to block. Black is also threatening White’s knight and bishop with two bishop moves, so White decides to play bishop and queen cards.

Black decides to save the queen for next turn, so they won’t have to leave it on the table. Instead, they play the bishop to stop White from threatening the king or bishop. White’s only two-move threat on the king is the knight, which they can’t play this turn, so White plays a rook to avoid any chance of both cards matching and skipping a turn where they have more information.

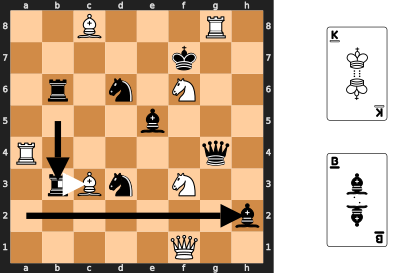

When the cards are revealed, the bishops cancel each other, leaving Black with two rook moves, then White with two queen moves. Black uses the rook card to move a pawn and then a rook: moving the h7 pawn forward two, then following it with the rook. White decides not to capture the black queen or the black rook, because the queen would almost certainly be captured next turn. Instead, they move the c2 pawn and bring the queen out that way:

Rules Quiz

Here are some examples that you can use to check if you understand the rules.

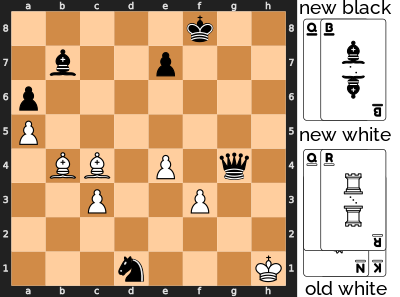

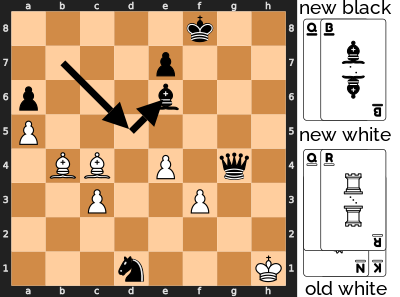

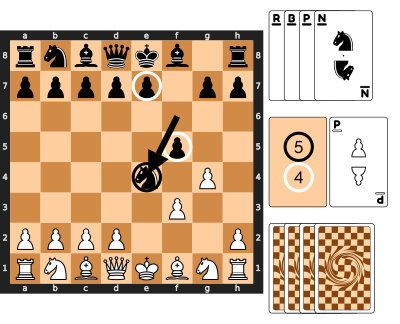

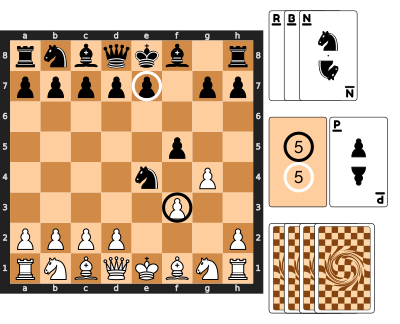

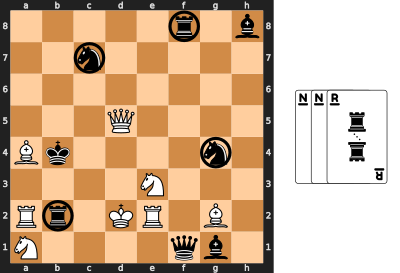

With these cards revealed, Black should be careful. There’s a move that seems to protect their queen and threaten the white king, but actually lets White capture the black king. See if you can find the move to avoid and a better option:

Here’s the move that might look good, but gives the game to White:

Because the two queen cards cancel each other out, Black gets to play the bishop card twice, then White gets to play the rook card twice.

Because Black takes both of White’s movable pawns at e4 and f3, the bishops are now White’s least valuable, movable piece type, and White can use any card to move them. White can capture the pawn at e7, and the king at f8.

Here’s a better move that will probably lead to a win for Black in the next turn or two:

As tempting as it is to capture a pawn or two, blocking your own last pawn can make all your cards more powerful. Here, it lets Black move the knight next turn with any card. As long as they can avoid giving White a double bishop move, they should be able to capture the black king with any two cards.

Most games will end with a double move to capture the king, but if you can survive until most of the pawns are captured or blocked, be very careful of the last pawn or two and the transition to freely moving more valuable pieces.

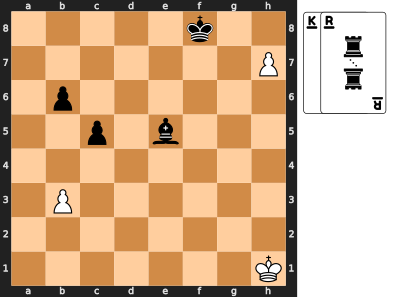

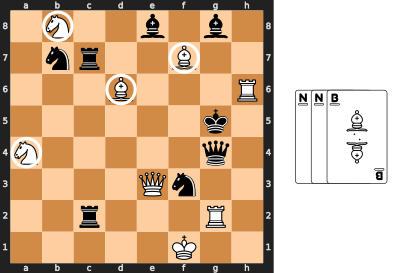

The challenge in the next example is to find a winning turn for White:

The solution is to remember that a pawn can be promoted to any other piece when it reaches the back rank. There are two ways that black can try to stop White: move the bishop to block at h8 or play a queen card to block the queen that the pawn will get promoted into. To avoid the blocking bishop, White can play a bishop card. To avoid getting the new queen blocked, White can play a rook card and promote to a rook instead:

Adrenaline Chess

What if taking your opponent’s piece frightened the others so much that they became more aggressive? Every time you take a piece, you have to choose one of the remaining pieces to get an adrenaline rush, and adrenaline can make any piece a king. This game adds a little chaos to chess, and accelerates the end game.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a standard set of 24 checkers. The checkers must be stackable, and you must be able to stack a chess piece on top of the checkers. Coins or poker chips would also work, as long as they fit inside the chess board squares.

Setup

Set up the chess pieces in the standard start position, and randomly choose who will play white. Place the checkers beside the board.

Play

All the regular chess rules apply, plus you must give an adrenaline rush after captures. If you captured one or more pieces, end your turn by placing a checker under one of your opponent’s remaining pieces. The colour of the checker doesn’t matter, and you may stack multiple checkers under a piece.

In the following example, white just captured a pawn with the bishop, and finishes the turn by adding a checker under the pawn at h7.

To move a piece with checkers under it, you must make a regular move for that piece, and bring the checkers along. Then you may use up one of the checkers under that piece to make an extra move like a king. Remove a checker from the stack, and move the rest one space in any direction. If that piece still has checkers under it, you may continue making extra king moves until the piece runs out of checkers.

The extra moves may capture pieces, but you only ever add one checker per turn. When you capture an opponent’s piece, your capturing piece keeps any adrenaline the captured piece had, and may immediately use the adrenaline.

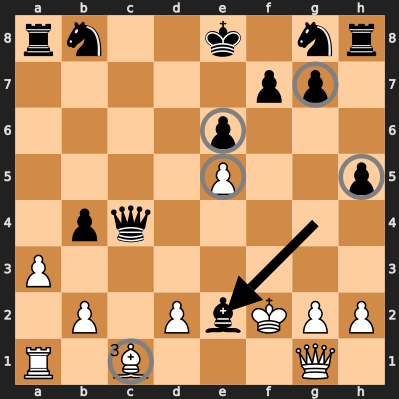

For example, here is a strange checkmate that uses white’s adrenaline to threaten the white king. Black has just captured a pawn, and has spent the last few turns pumping a trapped bishop full of adrenaline. Adding a third checker to the stack at c1 would seem to make the bishop a threat to the black queen, but it must make a regular move before it can start using the adrenaline. White has been forced to keep the king retreating, and hasn’t been able to move the pawns that would free the bishop. The black queen on the other hand, will be able to capture the bishop on the next turn, and then use those three checkers to capture the king at f2, possibly capturing the pawn at d2 along the way. Moving the king to e1 or e3 would still be in range for the queen. e2 would be a direct capture by the queen, f1 and f3 could be captured by the queen or the black bishop. g3 might give a glimmer of hope, until you notice that the black pawn at h5 has a checker. It is checkmate.

You may not castle, if either the king or the rook has checkers. During castling, you may not move your king through squares that could be attacked by extra moves. You may capture a pawn en passant at the usual square after a regular move of two squares. You may not capture en passant if the pawn used an extra move, and you may not use an extra move to capture en passant. A pawn that moves to the back rank immediately promotes, and may continue making king moves, if it still has checkers. You may not move a piece to reveal a check on your king, even if you then use an extra move to block the check again.

Winning

Win by checkmate, as in regular chess, but you may use extra moves to threaten the king.

Tar Pit Chess

Your checkers can cover your opponent’s pieces in tar to slow them down, and your cards limit where you can play those checkers.

Equipment

A standard chess set, a standard checkers set, and a deck of chess cards. (See how to turn standard playing cards into chess cards in appendix A.)

You must be able to stack a chess piece on top of a checker. Coins or poker chips would also work, as long as they fit inside the chess board squares. You need 12 each of two colours.

From the deck of cards, use one card to represent each piece, plus you also need two cards of each colour to represent checkers. That should make 36 cards in total, put the rest of the deck aside.

Setup

Set up the chess pieces in the standard start position, and randomly choose who will play white. Place 6 light checkers in front of White and 6 dark checkers in front of Black. Keep the extra checkers in a separate pile, but within reach.

Shuffle the deck and deal 6 cards to each player. Look at your cards, but don’t show them to your opponent. Place the rest of the cards in a draw stack.

Play

Your turn has up to four parts:

- You must move a chess piece.

- If the piece you moved has your own checker under it, you may throw the checker under a neighbouring piece.

- You may play a card to add a checker.

- Finally, draw cards until you have one card for every checker in front of you.

Moving and Throwing

Chess pieces move normally, unless they are stacked on checkers. Pieces on checkers are modified as follows:

- Your piece on your checker is carrying a bucket of tar: after moving your piece normally, you may throw the tar at one of your opponent’s pieces or pass it to one of your own. Move the checker like a king, one space in any direction, to place it under another piece of either colour. Leave your chess piece where it ended its move. You can only move a checker under another piece, it can’t sit alone on a square.

- Your piece on your opponent’s checker is tarred: pawns cannot move at all, and other pieces move like pawns.

When you move a piece on a checker, it brings its checker along with it. If you move a tarred piece all the way to your back rank, remove the checker and return it to your opponent, a bit like promoting a pawn.

If your opponent adds a checker to your piece that’s already on your back rank, the opponent’s checker is immediately removed. If your piece had one of your own checkers, that’s also removed.

Adding and Capturing Checkers

After you finish moving and throwing, you may play one of your cards to add a checker. You may only add checkers of your own colour, and you may only add one to a piece that matches the card.

Checkers cards change how many cards and checkers you have. If you play your own colour checker card, place one of your extra checkers in front of you. Then draw cards until you have the same number of cards as you have checkers in front of you. If you play your opponent’s colour checker card, they have to return one of their checkers to the extra pile. It can come from in front of them or on the board. If they now have more cards than checkers in front of them, they must discard a card of their choice.

If there are no pieces left on the board to match a card, it can match any of your pieces.

Play your card to a discard pile next to the draw pile, and shuffle the discard pile to make a new draw pile if it runs out.

Say “No card,” if you choose not to play a card.

When you capture a piece, your piece keeps any checker that the captured piece was stacked on. Capturing a carrying piece leaves you tarred, and capturing a tarred piece leaves you carrying.

Drawing Cards

After moving a piece and possibly playing a card, draw cards until you have the same number of cards as checkers in front of you. In practice, this means that you only draw after checkers combine and get returned or after playing a checkers card.

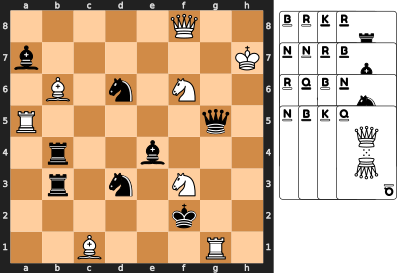

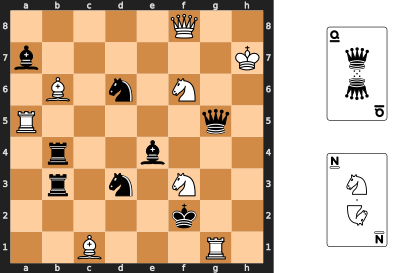

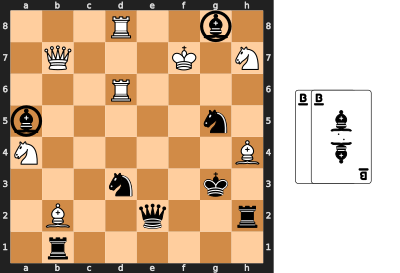

Here’s an example that shows all four parts of a turn:

It’s Black’s turn, and the diagram shows Black’s hand, as well as the card that White discarded on the previous turn. It also shows the back of White’s hand and each player’s stack of available checkers.

Black moves the knight to e4, and captures a pawn plus a black checker. The knight is now carrying a bucket of tar.

Black throws the tar that was just captured onto the pawn at f3. Now the pawn can’t capture the knight.

Black adds a checker at e4, by playing a black knight card.

Finally, Black has three cards and four checkers in front of them, so draws one card.

Multiple Checkers

Chess pieces may never have more than one checker under them. When you capture or add a checker, it may have to combine with a checker that was already there:

- Checkers of opposite colours cancel out. Return both to their owners.

- Checkers of the same colour repel each other. Return one to its owner, and keep one under the piece.

You may play a card to add a checker to a piece that already has your checker under it, but you immediately get the checker back. That can be a way to cycle through the cards, if you’re hoping to draw something better.

Here’s a different way to play a card in the example above. Instead of adding a checker to the knight at e4, Black plays the black pawn card to add a checker to the pawn at f5. The black checker immediately cancels out the white checker that was there, and both are returned to their owners.

Now, White can still capture the pawn at f5, but can’t also throw tar at the knight. Black still has the black knight card to add a checker on a later turn that might be in a good position to tar the white king.

Removing Tar

As a reminder, there are four ways to remove the checker from one of your tarred pieces:

- Play a card that matches the piece. Your added checker will cancel out the tar checker.

- Move one of your carrying pieces next to your tarred piece, and pass your checker to it. Your passed checker will cancel out the tar checker.

- Capture one of your opponent’s pieces that is tarred with one of your checkers. Remember that a tarred piece can only capture like a pawn: one space diagonally. The captured checker will cancel out the tar checker.

- Move the tarred piece like a pawn, all the way to your back rank, and then remove the checker.

Only the first two are possible for tarred pawns, because they can’t move at all.

Special Cases

You may not castle, if either the king or the rook have a checker.

Tarred pieces move like pawns, but do not move two spaces on their first move. A tarred piece may capture an enemy pawn en passant.

Winning

Win by checkmate, as in regular chess. Tarring the king makes it much easier to checkmate. Carrying a bucket of tar makes the king much harder to tar.

Variants

Make the game more predictable by using fewer checkers cards in the deck or fewer checkers during setup. Make it less predictable by using more. Handicap a player by giving them fewer checkers than their opponent. During setup, always deal one card for each checker.

Chess Golf

All the players try to work out the most efficient way to capture the chosen pieces, using all the wrong moves. This game is a series of puzzles, so let’s start with an example:

Every puzzle starts with the pieces spread around the board, and some cards choosing types of pieces. The goal is to make one chosen piece type capture the others in as few moves as possible. In this example, you have to make the white king capture one of the black bishops or make one of the black bishops capture the white king.

You might think that the bishop at e5 could directly capture the king, but in this game, the piece’s original movement is irrelevant. Pieces can only borrow a move from a neighbouring piece in the 8 squares immediately surrounding them, a bit like a golfer takes a golf club from the caddy standing next to them. That means that the bishop at e5 can only move like a knight and the king can’t move at all. Also, pieces can only borrow moves from a neighbour that’s the same colour, so the bishop at a2 can’t move at all.

Now that you know how the pieces move, here’s one possible solution:

The bishop moves like a knight to g6 and then moves like a king to h5. Then it borrows the queen’s move to capture the king at h2. The solution takes 3 moves.

You’re not limited to moving the two chosen piece types. Here’s a 3-move solution where a chosen piece type only makes the final capture move:

The white bishop uses the rook’s move to get out of the way, and then the black rook comes down to b3. The bishop at a2 can now use the rook’s move to capture the king.

There are solutions that help the white king capture a black bishop, but they take at least 4 moves.

Now that you’ve seen how to solve one of the puzzles, the rest of the rules explain how to solve a series of these puzzles with a group of players, keeping score like a round of golf.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a deck of chess cards. (See how to turn standard playing cards into chess cards in appendix A.) You’ll also need a pencil and paper for keeping score, a timer, and some coins. 4 coins are probably enough, and you can even play without them. A one-minute timer works well, although anything from 30 seconds to two minutes would be fine.

Setup

Place all the chess pieces except the pawns beside the board. Put the pawns away, you won’t need them.

Use the chess cards without the pawn cards, so you should end up with 16 cards.

Put the rest of the cards away, you won’t need them. Then shuffle the cards and place them next to the board. Draw one card at a time, placing the matching piece on the board. Start at a1 through h1, then wrap around to a2 through h2, all the way to h8. The pips in the centre of the chess cards or the table in appendix A show how big a gap to leave before each piece. That is, how many empty squares to leave before placing each piece.

Here’s an example with all the cards laid out in the order they were drawn, from the white bishop to the white queen. Check to make sure you agree with where the pieces were placed.

When all 16 pieces are on the board, randomly choose a dealer to shuffle the cards again.

Also choose a scorekeeper, and get them to write everyone’s initials at the top of the paper, leaving enough room for 9 scores and a course total.

Play

On the first turn, the dealer will draw two cards and place them face up next to the board where all players can see them. Check appendix A if you need to, and announce the two chosen piece types for this turn.

All players try to solve the puzzle in as few moves as possible. While solving, no one actually moves the pieces. Just visualize how the pieces will move and count how many moves you need to capture one of the piece types with the other.

When you find a solution and count the moves, start the timer, then put your fist on the table to show that you’re ready. When all the players have a fist on the table or when the timer runs out, the solving phase ends.

Now, everyone reveals their move count at the same time. Bang your fist on the table as you count “one, two, three.” As you say “three,” everyone puts out a number of fingers to show how many moves they need. The scorekeeper writes down everyone’s number as their score for this hole. If you think it’s impossible, or you just couldn’t find a solution, keep your hand in a fist as a zero.

The player with the fewest moves, but not zero, must now demonstrate the path. If some players are tied for fewest, start to the dealer’s left and go around to the left until you reach one of the tied players. That player must demonstrate. It can be helpful to start by placing coins under all the pieces that you’re going to move, so you can reset if you get confused.

Players should not be allowed to hesitate more than a few seconds while demonstrating. Be kind, especially to younger players, but they can’t sit and try to solve it at this point.

If the player can’t demonstrate their path, then they get the maximum of all the other players’ numbers, plus a one-point penalty. Reset the pieces to where they started and get the player with the next lowest number to demonstrate.

If some players say it’s impossible, let the player with the lowest nonzero number demonstrate. If they are successful, then all the players with a zero get the maximum number plus a one-point penalty.

After a successful demonstration, leave the pieces in their final positions, and add any captured pieces back to the board in any empty squares. Remove the coins, if you used them. The scorekeeper adds any penalty points for players who failed to demonstrate or thought it was impossible when it wasn’t. Pass the deck to the player who demonstrated, and they become the new dealer.

If everyone thought it was impossible, everyone gets zero points, and the same dealer deals again.

Special Move

The basic moves are to borrow a move from a neighbouring piece of the same colour. You may only capture one of the chosen piece types with the other one. No other captures are allowed.

In addition, there is one special move to help when you get stuck: if one of the colours has no pairs of pieces next to each other, then any piece of that colour may make a king’s move. Just because one piece has no neighbours of the same colour, it doesn’t necessarily get to make a king’s move. Only if a colour has no pairs of pieces next to each other, then all the pieces of that colour may make a king’s move.

For example, in the position below, neither the white knights nor the black queen has any neighbours of the matching colour. One way to move them is bringing in other pieces to borrow moves from. However, there’s an easier way.

Moving the bishop breaks the last pair of neighbouring white pieces, so the white knight at f6 can now use a king’s move to capture the black queen.

Difficulty Level

Once you’ve played a few holes, and all players understand the rules, the dealer may choose to increase the difficulty level on any hole by dealing three cards instead of two. One of the chosen piece types must capture both of the others.

Game End

Continue dealing new cards each turn until you have played 9 turns. If you don’t have enough cards to deal, shuffle the discard pile back in before you deal. Add up the points for all 9 turns, and award the game to the player with the lowest score.

A tie goes to the best dressed player.

Problems

Here are some positions that are more challenging than average. The chosen pieces are circled, and solutions are given at the end of the book. See if your solutions are as short.

Problem 1

Problem 2

Problem 3

Crowded House

Two teams of two play, with each player moving the pieces of their colour on the left or right half of the board. As usual, white moves first, then alternates with black. Each king-side player takes the first move for their team, then alternates with their partner.

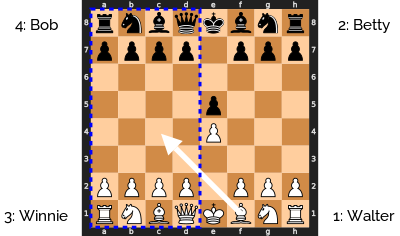

In the following example, Walter plays king-side white, Winnie plays queen-side white, Betty plays king-side black, and Bob plays queen-side black. Then the play order would be Walter, Betty, Winnie, Bob, Walter, Betty, and so on.

Setup

Place two white pawns and two black pawns in a bag, box, or cupped hands so the other players can’t see them. Have each player draw a pawn without looking to decide which two will play white and which two will play black. Teams can then decide which player will play king side and move first.

Set up the chess pieces in the standard start position.

Rule changes

The key rule is that you may only move a piece that either

- starts on your side of the board, or

- ends on your side of the board.

In this example, Winnie may move any piece that starts or ends on the queen side of the board, shown by the dashed rectangle. She may move the bishop as shown by the arrow, because it ends up on the queen side of the board. Winnie may not move the bishop to e2, because it would start and end on the king side.

If a player has no pieces on their side and can’t move any pieces to their side, they move nothing on that turn.

The rest of the rule changes flow from whether a piece may be captured immediately. A king may move into check or castle out of check, if the next player can’t make the capture. En passant capture only works if the pawn is captured immediately after its first move.

Winning

Win by check mate, as usual, but remember that the next player on the attacking team has to be able to make the capture.

Talking

This game shouldn’t be taken too seriously, so feel free to chat with your partner, but remember that the other team is listening. Any discussion should be heard by both teams, so no secret codes or second languages! Of course, players should also feel free to ignore their partner’s advice.

Cooperative Chess

If you don’t like battling your friend across the board, you can team up against the game itself. A line of cards limits what you can capture, and you work together to capture as many pieces as you can, with bonus points for each type of piece you eliminate.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a deck of chess cards. (See how to turn standard playing cards into chess cards in appendix A.)

Setup

- One player stands the chess pieces in the standard start position.

- Meanwhile, the other player shuffles the 32 cards,

- deals 2 to each player, and

- places the rest of the cards next to the board as a draw pile.

- When the chess pieces are set up, the first player secretly places a white pawn in one hand and a black pawn in the other. The other player then chooses a hand to decide their colour.

Play

White plays the first turn, and then players alternate. Each turn has four possible steps, in this order:

- You must play a card from your hand to a face-up line beside the draw pile. Add to the end away from the draw pile.

- You may make a non-capturing chess move.

- You may make multiple capturing chess moves, if the cards allow.

- You must draw a card to bring your hand back to 2, unless the draw pile is empty.

Three things can also happen to the cards immediately during your turn:

- If you ever draw or deal a king card, immediately add it to the face-up line and draw a replacement card.

- If there are ever 4 cards in a row of the same colour in the face-up line, they get recycled, as described below.

- A pawn and its card can get promoted, as described below.

The chess pieces make the same moves as in regular chess, but you can only make a capturing move if a card like the capturing piece is beside a card like the captured piece in the face-up line.

When you capture a piece, remove the piece from the board, and move the captured piece’s card from the face-up line to the discard pile. If you can make another capturing move that also follows the rule above, you may continue, even by moving a different piece.

As an example, imagine that Black has a black knight card and a white pawn card in hand with the following position:

They can play their pawn card, move the bishop to e6, and then capture both pawns. The bishop card is able to capture using the pawn card to its left and the pawn card to its right. It could not continue to capture the pawn at g2, because the remaining pawn card is black.

After the captured cards are removed, only the black pawn and bishop cards are left in the face-up line.

If White now has a white pawn, knight, bishop, or queen card, they can play that and capture the black bishop. Otherwise, they can try to set up a future capture.

If you ever make a four-in-a-row group of cards (or more) all the same colour, you must recycle them. You can make the group by playing a card to the end of the face-up line, or by capturing a card in the middle of the group. To recycle the group, take all cards in the group out of the face-up line, and shuffle them face down. Take one card out of the group, and place it to the side, out of the game. Shuffle the rest of the group back into the draw pile. Do the recycling without looking at the card faces, so you don’t know which card got removed. Recycling can be helpful to extend the game and unclog the face-up line, particularly when there’s a king in the way, but be careful you don’t lose both king cards, which would lose the game.

You may only move a pawn to the last rank if it has a matching card in the face-up line. Promote the pawn to any other piece type that has already been captured. Move the pawn’s card from the face-up line to the discard pile, then find the promoted piece’s card in the discard pile, and place it anywhere in the face-up line. That can be an effective way to capture cards that are stuck behind a king’s card. If a pawn captures a piece as it moves to the back rank, discard the captured piece’s card as normal, then deal with the promotion.

Castling is allowed. En passant capture is allowed. All individual moves must be legal chess moves, with this exception: you may move a king into check or leave it in check.

Winning

The game ends immediately when you capture a king. You then get a point for each piece that you captured, plus ten bonus points for each piece type that was completely removed from the board, both colours. For example, if you captured 23 pieces, including both queens, all four bishops, and a king, but still had at least one pawn, one knight, one rook, and the other king still on the board, then you would score 43 points.

Anything lower than 32 points is a loss, anything higher than 50 points is great! Keep track of your best score.

If the draw pile is empty, continue playing until you run out of cards in your hands. If you run out of cards without capturing a king, you get no bonus points.

Talking

The game works best if players know something about each other’s cards, but not everything. They should feel free to ask each other yes or no questions about their hands and to discuss general strategy, but shouldn’t just reveal their hands.

Solitaire

To play solitaire, don’t have any cards in your hand. At the beginning of each turn, draw a card and add it to the face-up line.

By Other Designers

Half Alice Chess

Alice Chess is a popular variant invented by Vernon Parton in 1953, usually played with one set on two boards. Since I wanted all the games in this collection to be playable with one chess set, I found a way to play it on one board by placing the mirror pieces on checkers. I’m not the first to suggest this idea, but I think it makes it easier to see the connections between the two sets of pieces.

The main idea is that pieces switch back and forth between the two sides of a mirror, as in Lewis Carroll’s “Alice Through the Looking Glass”. This causes many surprising positions and interactions, well worth exploring.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a standard checkers set. For full compatibility with the original rules, you’d need 16 checkers of each colour, but I think it’s unlikely you’d ever need more than the standard 12.

Setup

Place the chess pieces in their standard opening position, give the light checkers to White and the dark checkers to Black.

Play

Pieces not on checkers are on one side of the mirror, pieces on checkers are on the other side of the mirror. Rules are as in orthodox chess, with these changes:

- The move must be legal under orthodox chess rules.

- Switch the moved piece to the other side of the mirror after it moves. (Add or remove a checker.)

- Pieces cannot capture pieces on the other side of the mirror, but they can move through squares that are occupied by pieces on the other side of the mirror.

- If you’re playing with 12 checkers each, then you must have a free checker in order to move a piece without a checker.

Winning

Place the opponent’s king in checkmate. A king may not evade check by switching to the other side of the mirror, because the move must be legal before the switch.

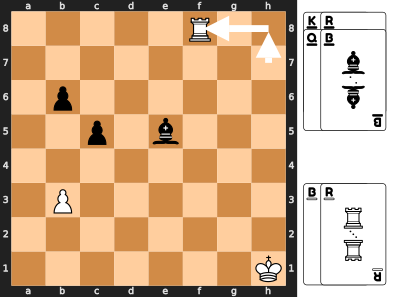

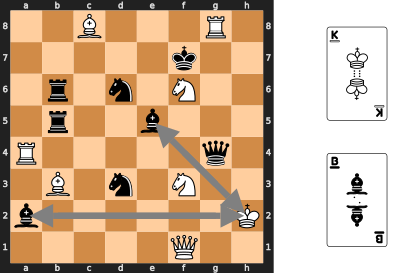

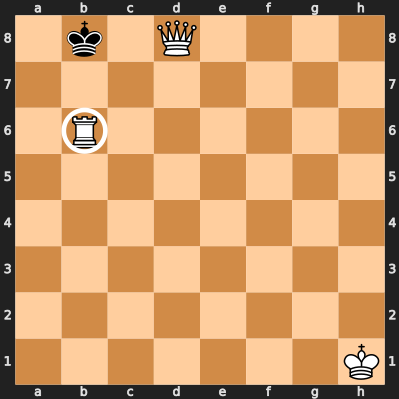

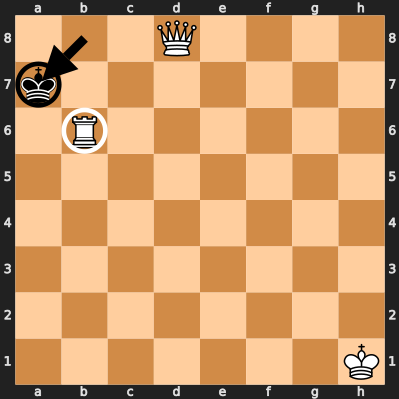

In this example, the king cannot move to a8, because it would still be in check by the queen before switching. It can’t move to b7, because it would be in check by the rook after switching.

The only legal move is to a7.

Chess960

This is probably the game in the collection that’s closest to standard chess; people organize Chess960 tournaments! It still reduces the need to study, because it takes away the standard “opening book”. One of the challenges to learning chess is that strong players have spent a lot of time studying standard openings. That can also make the early game feel like you’re following a script. Shuffling the starting position should make the standard openings much less important and make the play feel more creative.

Starting Position

The idea of shuffling the starting position has been around since the 1790s, but Bobby Fischer added some restrictions in the 1990s to avoid positions that strongly advantage one player:

- Pawns start in their regular position.

- The two bishops must be on different colours.

- The king must be between the two rooks.

- As in the standard starting position, black’s pieces are a mirror reflection of white’s.

With those restrictions, there are 960 possible starting positions. You can generate a random number and look up the position in a table, or use a website like mark-weeks.com to generate a position. You can also generate a random starting position with a standard deck of playing cards or with the deck of chess cards. If you have a standard deck, create a deck with the following ranks:

- 8, 8, 9, 9, 10, 10, Q, K

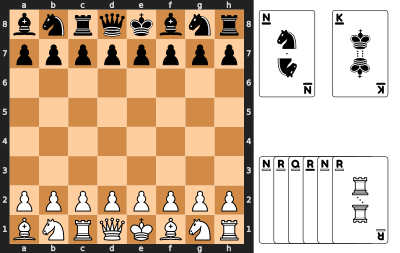

If you have chess cards, create a deck with all the white pieces:

- N, N, B, B, R, R, Q, K

Either way, you should now have a deck of eight cards. Use that deck to set up the chess pieces by following these steps:

- Take the two bishop cards or the two 9s out of the deck and set them aside.

- Shuffle the remaining six cards and deal them face down into two piles of three.

- Add one bishop or 9 card face down into each of the two piles. That should leave you with two decks of four cards each, call them deck 1 and deck 2.

- Shuffle deck 1 and deck 2, but keep them separate.

- Deal eight cards face up along the bottom of the board, alternating cards from the two decks, so the cards come from deck 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2.

- In the same order as those cards, place the white pieces along the first rank. If you used regular cards, place a knight for an 8, a bishop for a 9, a rook for a 10, and the queen and king for the queen and king cards.

- If both rooks are on the same side of the king, swap the king with the nearest rook.

- Place the pawns in their regular starting position, and make the black pieces mirror the white pieces.

Castling

The other change that Bobby Fischer made was to the castling rules. As usual, the king may castle with the rook to his right or his left. However, the two pieces’ end positions after castling are the same as for standard chess. So to castle with the a-side rook, white’s king would end on c1 and the rook on d1, no matter where they started. In the example above, white’s third move could be to castle.

As in regular chess, there are several restrictions before you can castle:

- The king and the rook must not have moved.

- The king’s starting square, ending square, and all the squares he moves through must not be under attack.

- All the squares the two pieces move through must be empty, except for the two pieces themselves.

The rest of the standard chess rules apply unchanged.

Synchronous Chess

There have been a few attempts to remove the first player’s advantage by making moves simultaneously, and this is my favourite. Its history is a bit murky, but my best guess is that it was designed in 1991 by Vitaly Korolev. Then Ralf Hansmann, Arnold J. Krasowsky, and Andrey Krasowsky removed some special cases and added an exchange of blows after the simultaneous moves.

Two Move Chess also has a simultaneous choice of which pieces to move, but then moves are made in a defined order.

Equipment

A standard chess set, plus paper and pencil for each player.

Setup

Start with the regular opening position.

Goal

Capture the opponent’s king, or checkmate it so it is under attack and has no safe move.

Play

The same moves are legal as in regular chess, but both players write down a move at the same time, then reveal them. Feel free to use any chess notation familiar to both players. The moves are resolved in one of three ways:

- If a move ends on a square that was occupied by a piece of the opposite colour, and that piece didn’t make a move at the same time, then it is captured as normal.

- If a move ends on a square that was occupied by a piece of the opposite colour, and that piece made a move at the same time, then it is not captured. This means that two pieces may swap positions, if they try to capture each other, and pieces sometimes move through each other.

- If both moves end on the same empty square, then both pieces are captured.

Remember that a move must be legal in regular chess, before the opponent’s piece moves.

After resolving the synchronous moves, check to see if an exchange of blows is possible. This happens if either piece has moved to a square that was attacked by an opponent’s piece before the move and is still attacked by the same piece. The opponent has the option to capture the piece that just moved. If they do so, check to see if the original player can now capture on the same square. This continues until no more captures are possible on that square, or a player decides not to capture. Each piece may only move once during an exchange of blows. The pieces that made simultaneous moves may participate in an exchange of blows, if they have a legal attack.

If both players have the option to exchange blows, they should write down their moves at the same time, then reveal them. To pass, just write an X.

If a king is under attack, it must move to a square that is not under attack before the move. Moving a piece to block the attack isn’t legal, because the attacker could move at the same time. If a king has no safe squares to move to, then it is checkmate. Castling out of check is not legal, because all moves must be legal in regular chess.

There is no “en passant” capture. If you don’t know what that is, you can safely ignore it.

If both kings are checkmated at the same time or captured at the same time, the game is a draw.

If a king and any other piece move to the same square, both are captured and capturing the king is a win.

All the regular causes of draws are still in effect: repeated positions or many moves without any pawn progress.

Appendix A

Several of the games require a deck of cards to match each chess piece. There are a few options to choose from:

- Use standard playing cards, and memorize which cards match which pieces, as shown in the table below.

- If you don’t mind defacing a deck of cards, write the letters for the chess pieces on the cards, as shown in the table below. Press lightly to avoid marking the back of the cards.

- Download the chess deck PDF from https://donkirkby.github.io/chess-kit, print out the cards on card stock, then cut them out.

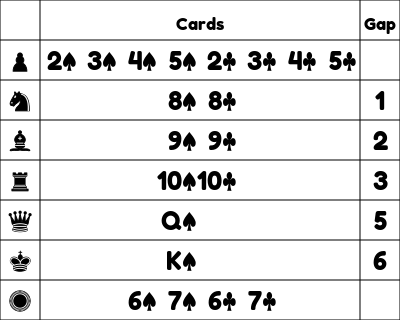

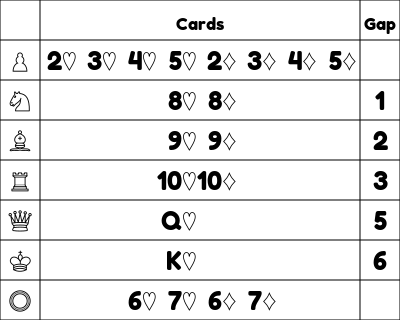

If you’re going to use standard playing cards, these tables show the cards that match each type of chess piece or checker. Some of the games also use cards to randomly lay out the pieces on the board, and these tables show how big a gap to leave before each type of piece. That is, how many empty squares to leave before placing the piece.

The cards with small numbers match pawns. Kings and queens are obvious, and the other pieces are sorted by strength to match the number cards from 8 to 10. In the games that use checkers, they match 6s and 7s.

Black cards match black pieces:

Red cards match white pieces:

Solutions

Chess Golf Solutions

Here are the solutions to the Chess Golf problems.

- d3b5, a5c6, c6e7, g3g4, g5f6, e7g8

- e3g3, g1b6, c7f4, g4e5, f4e6, e6f8, f8g7, g7e5

- g2f2, e3e7, f7b3, a4d7, d7d6, d6d8, d8b8

Contributing

Know some other lighthearted chess variants? Ideas to share? Get in touch at https://donkirkby.github.io/chess-kit.

Zombie Chess, Masquerade Chess, Two Move Chess, Adrenaline Chess, Tar Pit Chess, Chess Golf, Crowded House, and Cooperative Chess are original games designed by Don Kirkby.