Introduction

These are new games that aren’t ready yet. You can try them out and let me know what you think.

Table of Contents

- Secret Chesswords is a cooperative game where you use clue words to guide the other player’s moves. (2 players, chess set, letter tiles, and deck of cards)

- Split-Brain Chess is a battle between partnerships, if they can cooperate well. (4 players, chess set, a coin or checker, plus a piece of paper, a pen, and a pencil for each player)

- Gravity Chess has both players move in the same direction, trying to stack pieces higher. (2 players, chess set, and deck of cards)

- Parade Chess Solitaire requires pieces to move each other into a connected group. (1 player, chess set, and deck of cards)

- Booster Chess uses cards to boost your chess army. (2 players, chess set, checkers set, and deck of cards)

- Neighbour Chess Solitaire moves pieces using their neighbours’ moves to form one connected group. (1 player, chess set, and deck of cards)

- Cloak and Dagger Chess is a game where you disguise your chess pieces as checkers, then try to identify your opponent’s pieces. (2 players, chess set, checkers set, pen, and tape)

New Games

These games are in early development or playtesting. The rules might get more filled out or change based on feedback from players.

Secret Chesswords

A cooperative game for two, where you each need your partner to make certain moves. You can’t just tell your partner where to move, though. You have to give a clue to a word that starts and ends with the same letters that the move starts and ends on.

To reduce the number of possible moves, I wanted to base it on a simplified version of chess. I chose Los Alamos chess, which is a set of rules used by the first computer chess program, when computers weren’t powerful enough to play regular chess.

Design Questions

- How long can a clue be? (3 words are pretty easy, 2 words are pretty hard.)

- Can you tell your partner whether they made the move you wanted?

- Increase difficulty with checkers cards? Discard together with another card when the capture was made by your partner’s king.

Equipment

- a standard chess set

- a deck of chess cards (See how to turn standard playing cards into chess cards in appendix A.)

- letter planks (See how to make them in appendix B.)

Setup

Take a pawn of each colour, and hide one in each hand. Let your partner choose a hand to decide their colour.

Shuffle the six letter planks, mixing up their order, and which side is face up. Then lay the planks out to form a six-by-six grid. To make the light and dark checkerboard pattern work, you’ll probably have to turn some planks 180°.

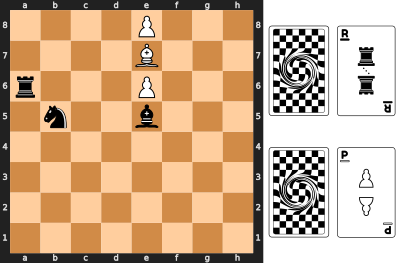

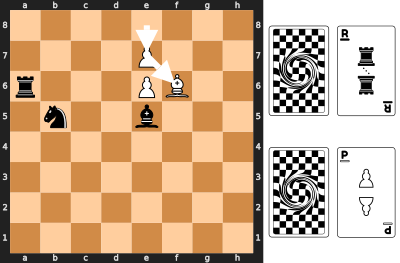

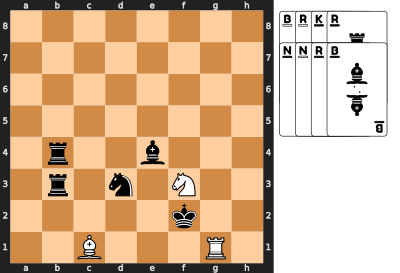

Los Alamos chess is played on a 6x6 board, without bishops, so put the bishops aside, along with two pawns of each colour. That leaves you with this starting position:

Remove the bishop cards from the deck, as well as two pawn cards of each colour, they won’t be used. Separate the remaining cards by colour, so each player has 12 cards of their partner’s colour.

Each player puts the king card aside and shuffles the other 11 cards. Then they deal three cards face down and shuffle them together with the king. Put the other eight cards on top, so the king is somewhere in the bottom four cards.

Finally, each player draws the top card from their deck, before their first turn.

Goal

You’re working with your partner to capture one of the two kings, without letting too many cards build up in your hand.

Play

White plays first, then Black, and so on. In each turn:

- The active player draws a card.

- The active player asks their partner to make a move.

- The active player makes a move.

- The active player must have fewer than four cards, or both players lose.

To keep your hand fewer than four cards, you can discard a card when you capture a piece that matches the card. You ask your partner to make a move that lets you capture one of their pieces on this turn or a later turn.

However, you can’t just tell your partner what move you want. You can only give a clue to the move you want. Look at your cards and decide on a move that you’d like your partner to make. Read the letter on the piece’s current square and the letter on the square that move will end on. Think of a word that starts with the move’s starting letter and ends with the move’s ending letter. Then give a clue for that word without saying any form of the word itself. The clue may be one word or a short phrase of up to three words.

When your partner asks you to make a move, think about the clue and say what you think the secret word is. Find a legal chess move that starts and ends with the first and last letter of the secret word, then make that move. The clue giver then tells you whether you made the move they wanted. If you didn’t, they can’t tell you what they wanted instead. Either way, they can’t tell you anything about future moves.

If you don’t know what move your partner is asking you to make, or you don’t want to make the move they’re asking for, you can choose your own move.

Captures

When you capture one of your partner’s pieces on either player’s turn, discard one of your cards that matches the piece, if you have one. You may only capture a piece if you have the matching card.

Legal Moves

All moves must be legal chess moves, with these changes for Los Alamos Chess:

- Pawns cannot move two squares on their first move.

- No castling.

- Pawns cannot promote to bishops.

In addition to the Los Alamos changes, there’s no such thing as check or checkmate, since you’re working as partners.

Game End

The game either ends as a win when one of you captures a king, or as a loss when one player has four or more cards at the end of their turn.

Increasing Difficulty

When you get about halfway through the game, decide with your partner if you want to make it more challenging. If so, swap draw decks so that you each draw cards of your own colour. To discard a card of your own colour, your partner must capture one of your matching pieces. If they guess wrong, and you don’t have a matching card, then they must draw an extra card.

If you want even more of a challenge, here are some changes you can make:

- Give two-word clues.

- Start with cards of your own colour.

- Draw more cards during setup.

Split-Brain Chess

This is another chess game for four players, this time more chaotic than Crowded House. The players each have to contribute half the move, but it gets messy when they don’t agree.

Because chaos is frustrating in a long game, I wanted to base it on a simplified version of chess that plays more quickly. I chose Los Alamos chess, which is a simplified set of rules used by the first computer chess program, when computers weren’t powerful enough to play regular chess.

Design Questions

- Los Alamos chess, or Tic Tac Chec?

- Is it more fun for the mover to draw a movement vector, instead of circling a target? It’s definitely simpler to circle a target.

- Is it more fun to let the opponents choose whether piece or target is flexible?

Equipment

A standard chess set, a checker or a coin, plus a piece of paper, a pen, and a pencil for each player.

Setup

Los Alamos chess is played on a 6x6 board, without bishops, so put the bishops aside, along with two pawns of each colour. You can use a regular chess board, just don’t use the squares along all four edges. Place the checker or coin in the black king’s corner. The checker reminds players to ignore the outer squares, and also reminds players about the movement rules, described later. That leaves you with this starting position:

Put the two extra pawns of each colour in a bag or box, and let each player take a pawn without looking to choose the colour they will play.

Each player should take a piece of paper, and write a 6x6 grid on it in pen. Label one side with a W for White and the opposite with a B for Black.

Play

The rules of standard chess apply, with these changes:

- Partners make a move together, as described in the next section.

- Pawns cannot move two squares on their first move.

- No castling.

- Pawns cannot promote to bishops.

Making a Move

To make a move, one partner is the chooser, who chooses which piece to move. The other is the mover, who decides where to move it. Each team has one partner on the king side of the board and one on the queen side of the board. The partner on the same side as the checker is the chooser.

Starting with the two white players, they both shield their paper grids from each other with a hand or a book, and circle a square in pencil. The chooser is circling the piece they choose to move, and the mover is circling the target square they want to move it to. Once they’ve both circled a square, they reveal their grids.

If the chosen piece can legally move to the target square, the white mover makes that move. If not, the black chooser chooses whether white must use the chosen piece or the target square. If they choose the piece, then the white mover must make a legal move with that piece. If that piece has more than one legal move, they must make the one that ends closest to the target square. If the black chooser chooses the target square, then the white chooser must choose a piece that can legally move to that square and move it there. If more than one piece can legally move to that square, they must choose the one that is closest to the one they originally chose.

When choosing the closest square or the closest piece, use “Manhattan distance”, or the number of steps between squares without making any diagonal steps. If more than one choice is the same distance, players may use whichever they prefer.

While writing down their moves, players must follow these rules:

- They may not say anything or look at their partner’s paper.

- The chooser must circle a square that has one of their pieces on it, and that piece must have a legal move.

- The mover must circle a square that at least one piece can legally move to.

- If either player circles an invalid square, they must circle the nearest valid square instead. If more than one valid square is the same distance, the opponents’ chooser may choose which one to use.

After the white team finishes their move, the black team uses the same steps to make a move. After the black team finishes their move, they slide the checker from the king’s corner to the queen’s corner, or vice versa. Then the steps repeat.

Winning the Game

As in regular chess, put the opponent’s king in checkmate to win the game.

Gravity Chess

This game was inspired by several video games that have pieces dropping down a well and stacking on the bottom. Its most unusual mechanics are that both players start on the same side of the board, and you move all your active pieces every turn.

Design questions:

- Can the end game be improved?

- Can we make it easier to keep track of which pieces moved? Go from the bottom up?

Equipment

A standard chess set and a standard deck of 52 cards.

Setup

Place all the chess pieces beside the board. Put away four pawns of each colour, you won’t need them. One player takes a pawn of each colour and hides one in each hand. The other player picks a hand and then plays that colour.

From the deck of cards, use one card to represent each piece, as shown in appendix A. To match the pieces, you’ll only need four pawns of each colour, so you should end up with 24 cards.

Put the rest of the cards away, you won’t need them. Separate the cards by colour, give the black cards and pieces to the white player and the white cards and pieces to the black player. Each player should shuffle their cards face down without looking at them.

Goal

Get more of your pieces stacked at the bottom of the board, and stack them in higher rows for more points.

Play

Each turn has three phases:

- Flip a card for your opponent.

- Move all your active pieces, so they end up at least one row closer to the bottom. However, you may capture a piece in the same row.

- Add your opponent’s piece that matches the card to the top row in any column.

Moving Pieces

Each turn, you must move all your active pieces, unless they are blocked by another piece or stacked on the bottom. Stacked pieces are explained below. When you move a piece, gravity pulls it down, so that the only legal moves are ones that end up at least one row closer to the bottom. There’s an exception for captures: you may capture an opponent’s piece with a legal move that ends on the same row or any row closer to the bottom. You may not capture stacked pieces, as explained below.

Pawns may either capture one space diagonally downward or move one space downward to an empty square. On their first move, they may move two spaces downward if both squares are empty.

White has no active pieces on the first turn, so has nothing to move.

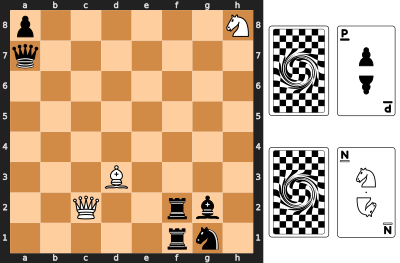

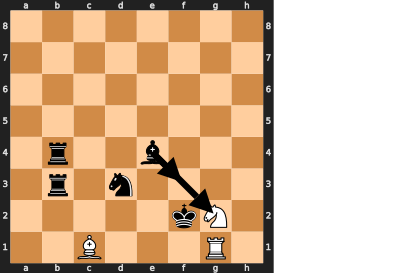

In this example, White has just flipped a black rook card, and has to choose which order to move their pieces.

If they move their bishop first, then the top pawn can also move.

If they move the top pawn first, they would say “This pawn can’t move,” and then move the bishop. Either way, the lower pawn can’t move.

Stacked Pieces

If a piece reaches the bottom row, it becomes stacked, and can’t be moved or captured. If all possible downward moves for a piece are blocked by stacked pieces, then that piece is also stacked, and can’t be moved or captured.

In this example, the two pieces on the bottom row are obviously stacked, but the only one stacked in the second row is the rook. The bishop can move down to h1, and the queen can move down to any of the three squares below it. If the rook weren’t between them, the queen could capture the bishop, because it’s not stacked. However, it can’t capture the stacked rook.

Game End

Turns continue until Black adds the last white piece, then White gets one last turn without flipping a card or adding a piece.

Count points for each player’s stacked and captured pieces. A captured piece is worth one point. A stacked piece on the bottom row is worth one point, on the second row is worth two points, and so on. The player with the most points wins. In case of a tie, look at the highest row with stacked pieces. The player with the most stacked pieces in that row wins. If still tied, continue looking at the next row down until you find a difference. If all rows are tied, the game is tied.

In this example, the unstacked pieces have arrows showing all possible downward moves.

To calculate the score, count the pieces. White has 2 captured pieces for 2 points, 1 stacked piece on the bottom row for 1 point, 3 stacked pieces on the second row for 6 points, 1 stacked piece on the third row for 3 points, and 1 stacked piece on the fourth row for 4 points. Black has 4 captured pieces for 4 points, 6 stacked pieces on the bottom row for 6 points, 1 stacked piece on the second row for 2 points, 1 stacked piece on the third row for 3 points, and 1 stacked piece on the fourth row for 4 points. That makes a total of 16 for White and 19 for Black, so Black wins.

Parade Chess Solitaire

Half the chess pieces are on parade, giving each other orders, and they have to form up into one connected group. Keep adding pieces until you have enough to start, but you get more points for fewer pieces making fewer moves.

This is another game with a similar mechanic to Chess Golf, and it’s a bit dry.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a standard deck of 52 cards.

Setup

Place all the chess pieces except the pawns beside the board. Put the pawns away, you won’t need them.

From the deck of cards, use one card to represent each piece, as shown in appendix A. You don’t need the pawn cards, so you should end up with 16 cards.

Put the rest of the cards away, you won’t need them. Then shuffle the cards and deal them into two piles of eight next to the board. From one of the piles, draw one card at a time, placing the matching piece on the board. Starting at a1 through h1, then a2 through h2, and so on until you’ve placed eight pieces on the board. The table in appendix A shows how big a gap to leave before each piece. That is, how many empty squares to leave before placing each piece.

Here’s an example with all the cards laid out in the order they were drawn, from the 9 and 10 of hearts to the 9 of spades. Check to make sure you agree with where the pieces were placed.

Play

Take the remaining stack of eight cards, and spend them on actions to bring the chess pieces together. Each card can be spent on one of two actions:

- Move a piece. Take the top card from your deck and play it face down next to the discard pile from the setup phase. Then use one of the pieces on the board to move another piece. A piece can move any piece of the opposite colour from a square that it could attack in regular chess. Pick up the piece that you want to move, and then place it in another square that piece moving it could attack. For example, black knight at d3 could move the white bishop from c1 to b2, e1, f4, e5, or c5. The king could move either of the white pieces next to it to any of the other spaces next to it.

- Add a piece. Take the top card from your deck and play it face up onto the discard pile from the setup phase. Add the piece as in the setup phase, leaving the regular gap after the piece that is in the occupied rank farthest from 1 and in the rightmost file of that rank. In the example above, if you played the 8 of diamonds, you would play a white knight at g7 to leave a one-square gap after the black bishop.

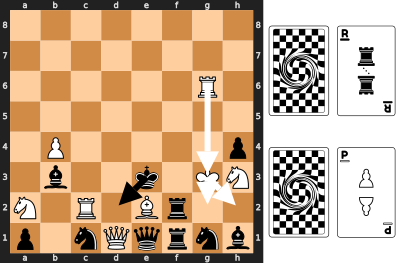

Here’s an example of using the black bishop at e4 to move the white knight from f3 to g2:

Winning

If you can get from any piece to any other piece on the board only stepping on neighbouring pieces, then you have formed one connected group and you win. Diagonal neighbours don’t count. Count how many cards you have left in your hand, and that’s how many points you win.

If you run out of cards before you form one connected group, pick up all 16 cards, and use them to count negative points until you form a connected group. You may only move pieces and not add any.

Broken Games

These ideas seemed promising, but didn’t work at the table. Maybe I’ll come back to them, if I get inspired. Masquerade Chess seemed broken for 15 years, before I had the idea to hide only the capture moves.

Booster Chess

Start every game with a booster pack of cards to make your pieces better or hobble your opponent’s pieces.

This was an attempt to add the chaos of cards to Adrenaline Chess, but players would often get good enough cards that they could stomp their opponent in under ten moves. It also ended up feeling too similar to Adrenaline Chess. I solved both problems by dropping the boost and keeping only the hobble to make Tar Pit Chess.

Equipment

A standard chess set, a standard checkers set, and a standard deck of cards.

The checkers must be stackable, and you must be able to stack a chess piece on top of the checkers. Coins or poker chips would also work, as long as they fit inside the chess board squares. You need 6 each of 2 colours.

From the deck of cards, use one card to represent each piece, as shown in appendix A. You also need two cards of each colour to represent checkers, so add the sixes to the deck. That should make 36 cards in total, put the rest of the deck aside.

Setup

Set up the chess pieces in the standard start position, and randomly choose who will play white. Place 6 light checkers in front of White and 6 dark checkers in front of Black. You won’t need the rest of the checkers, so put them aside.

Shuffle the deck and deal 6 cards to each player. Look at your cards, but don’t show them to your opponent. Place the rest of the cards in a draw stack.

Play

Your turn has up to four parts:

- You must move a chess piece.

- If you moved a boosted piece, you may spend checkers to also move it like a king.

- You may add a checker, by playing a card.

- Finally, draw cards until you have one card for every checker in front of you.

Chess pieces move normally, unless they are stacked on checkers. Pieces on checkers are modified as follows:

- Your piece on your checker is boosted: after moving it normally, you may move it like a king, one space in any direction. If you make the king’s move, remove the checker and place it in front of you. If the piece is on more than one checker, you may continue spending checkers to make more king’s moves on the same turn.

- Your piece on your opponent’s checker is hobbled: pawns cannot move at all, and other pieces move like pawns. If it is on more than one checker, it’s still hobbled, but no worse.

If one of your pieces is on a black and a white checker, immediately remove one checker of each colour and return them to their owners. Keep removing pairs of black and white checkers, if there are more.

When you move a piece, it brings any checkers along with it, except a spent booster.

Adding and Capturing Checkers

After you finish moving, you may play one of your cards to add a checker. You may only add checkers of your own colour, and you may add one to a piece that matches the card.

Checkers cards match any piece of that colour, so you may use a black checker card to add one of your checkers to any black piece or use a white checker card to add one of your checkers to any white piece. If there are no pieces left on the board to match a card, you may use it to add one of your checkers to any piece of the card’s colour, just like a checkers card.

Play your card to a discard pile next to the draw pile, and shuffle the discard pile to make a new draw pile if it runs out.

When you capture a piece, your piece keeps any checkers that the captured piece was stacked on. Capturing a boosted piece leaves you hobbled, but capturing a hobbled piece leaves you boosted! Don’t forget that opposite colour checkers immediately cancel each other and get returned to their owners.

Besides neutralizing a hobble checker by adding one of your own, there is another way to remove it: get it to the back rank of the board. If you do, just remove the hobble checker and return it to your opponent.

Drawing Cards

After moving a piece and possibly playing a card, draw cards until you have the same number of cards as checkers off the board. In practice, this means that you only draw if you spent a booster checker or received a hobble checker from your opponent.

Special Cases

You may not castle, if either the king or the rook is boosted. During castling, you may not move your king through squares that could be attacked by booster moves. You may not move a piece to reveal a check on your king, even if you then use a booster move to block the check again.

Hobbled pieces move like pawns, but do not move two spaces on their first move. You may capture a pawn en passant at the usual square after a regular move of two squares. You may not capture en passant if the pawn used a booster move, and you may not use a booster move to capture en passant. A pawn that moves to the back rank immediately promotes, and may continue making booster moves if it is still boosted.

Winning

Win by checkmate, as in regular chess, but you may use booster moves to threaten the king.

Variants

Make the game more predictable by using fewer checkers cards in the deck or fewer checkers during setup. Make it less predictable by using more. Handicap a player by giving them fewer checkers than their opponent. During setup, always deal one card for each checker.

Neighbour Chess Solitaire

Pairs of chess pieces help each other across the board until you gather them all into one connected group. Keep adding pieces until you have enough to start, but you get more points for fewer pieces making fewer moves.

This game might not be broken, but it inspired Chess Golf, and they’re too similar to keep both.

Equipment

A standard chess set and a standard deck of 52 cards.

Setup

Place all the chess pieces except the pawns beside the board. Put the pawns away, you won’t need them.

From the deck of cards, create two smaller decks. The first is a deck of 16 cards for the chess pieces, as shown in appendix A. You don’t need the pawn cards.

The second is a deck for the positions on the board: 2 - 6 of Hearts, Diamonds, Spades, and Clubs.

Put the rest of the cards away, you won’t need them. Then shuffle each deck and place them next to the board as the two draw piles.

Play

In the first part of the game, you add pieces to the board, as directed by the two decks of cards.

- Flip over the top card of the pieces deck and place it on a discard pile.

- Take the piece that matches that card, and hold it above the board. If it’s the first piece, hold it above the bottom left corner. Otherwise, hold it above the last piece you added. (Check the discard pile, if you forget which piece you added last.)

- Flip over the top card of the positions deck and place it on a second discard pile.

- Now move the piece from the square it’s above to a new square and add it to the board. If the position card is a red card, move the piece that many squares to the right, otherwise move the piece that many squares up. If you move off the edge of the board, loop around to the opposite side and keep counting.

- If the space you move to is occupied, you may move to any of the 8 neighbour spaces. If all of them are occupied, you may move to any of their neighbours, and so on. You may not wrap around the edge of the board in this case, so edges and corners have fewer than 8 neighbours.

After adding any piece, you may choose to stop adding and try to move the pieces into one connected group.

- Before each move, spend a card from one of the draw piles to a discard pile.

- Then move one of the chess pieces. However, it doesn’t use its usual move. Instead, use the move of one of its neighbours of the same colour in the 8 squares around it. If a piece has no neighbours of the same colour, it cannot move.

Winning

If you can get from any piece to any other piece on the board only stepping on neighbouring pieces, then you have formed one connected group and you win. Count how many cards you have left in the two draw piles, and that’s how many points you win.

Cloak and Dagger Chess

Pawns are played as usual, but all other pieces are replaced by numbered checkers. Players have to deduce which of their opponent’s pieces are which, and then capture the king.

Setup

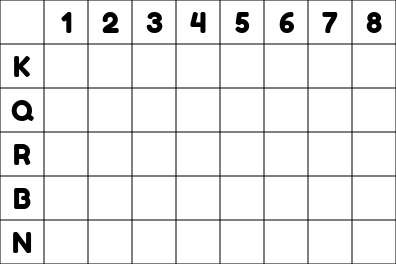

Place all the pawns in their regular position, then use tape or stickers to write the numbers 1 to 8 on checkers for each player. Put the black checkers on black’s back row and the light checkers on white’s back row. Finally, write two grids like this to secretly record your pieces and deduce your opponent’s:

Obviously, you don’t have to put the pieces in their standard starting positions, but you do have to have a standard set of pieces. (You can’t give yourself three queens!) You also have to follow the same restrictions that Chess960 puts on its random starting positions:

- Place your king somewhere between your two rooks.

- Place one of your bishops on a light square and one on a dark square.

Write a circle for each piece you know, and an X for each piece you know is impossible. You might want to write X’s for your own pieces as your opponent learns which of your combinations are impossible.

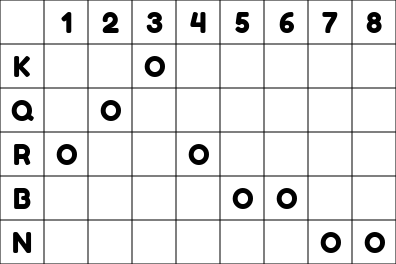

Here’s one possible way to fill in your grid at the start of the game:

At the start of your turn, you may guess the identity of one of your opponent’s checkers. If you guess correctly, you may make a bonus move after your regular move. Your bonus move may be either a regular pawn move or to take back a pawn that your opponent captured and drop it on an empty square in your second rank. If you guess incorrectly, your opponent may make the same kind of bonus move before their next turn.

At the end of your turn, you may replace any number of your checkers with their uncloaked chess pieces.

If one of your checkers is captured, tell your opponent which piece they captured.

Winning

Win by capturing a cloaked king or putting an uncloaked king in checkmate. You might have to uncloak some of your pieces to show the checkmate.

A cloaked king may move into check, stay in check, or castle out of check, because the opponent doesn’t know it’s in check. Castling is the same as in Chess 960: the king and rook end up on the same squares they do in standard chess. All spaces between their start position and their end position must be empty, except for the king and the castling rook. All spaces between the king’s start and end positions must not be under attack, if the king is uncloaked.

Design Problems

Because you don’t know how your opponent’s pieces capture, you never know if you’re safe. You’re not even safe from the pawns, because your opponent can sometimes make two pawn moves.

Maybe it’s too similar to Masquerade Chess to begin with.

Appendix B

Secret Chesswords is played on a 6x6 board with a letter on each square, and there are a couple of ways to create one.

- If you already have a deck of cards with letters from another game, collect a set of 36 cards something like this: A, A, C, D, D, E, E, F, F, G, H, H, I, L, L, M, N, N, O, O, O, R, R, S, S, S, S, S, T, T, T, T, T, T, W, Y. Then shuffle the cards and deal them out in a 6x6 grid.

- Download the chess planks PDF from https://donkirkby.github.io/chess-kit, print out the two grids on paper, then glue one to each side of a piece of cardboard, and cut the rows apart.