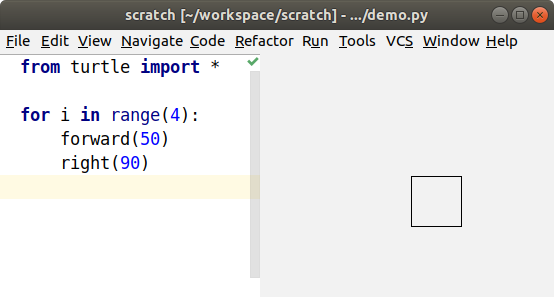

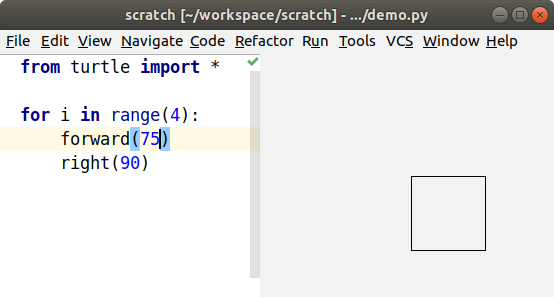

Live Coding in Python lets you run your Python code as you type it. For example, this code draws a square that’s 50 pixels wide and 50 pixels high.

When I change the forward distance to 75, the square immediately changes. I don’t even have to save the file.

In this tutorial, I’ll demonstrate these features:

- live turtle graphics that make a fun learning tool

- a live coding display that can be used with regular code to show you what’s happening inside it

- live unit tests

- matplotlib previews

- pyglet previews

To try it yourself, follow the PyCharm installation instructions, then type some turtle graphics code, as in the example above. Finally, from the Run menu, choose Start Live Turtle. You should see a preview of your turtle graphics. You can also watch my demo video.

Live Turtle Graphics

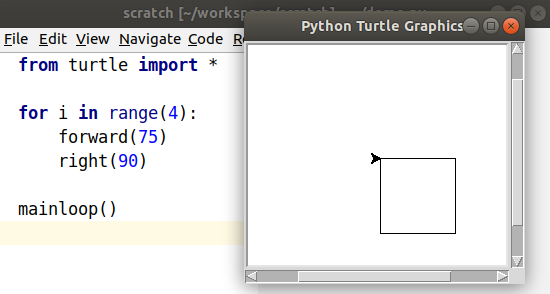

Python already comes with a turtle module, so what’s the difference? To use the

regular turtle, I need to add a call to mainloop(), and then I need to save

and run. Every time I make a change to the code, I need to save and run to see

the result. Of course, I don’t do that every time. Instead, I predict the result

by running through the code in my head. One of this project’s main goals for

live coding is to let programmers’ brains focus on writing code instead of

running code. If you can see the code’s results laid out in front of you, you

don’t have to hold it all in your head.

Still, I sometimes like to run the regular turtle graphics code to see the animation of how the turtle moves along its path. The same turtle code will run in live coding mode as in the regular turtle window.

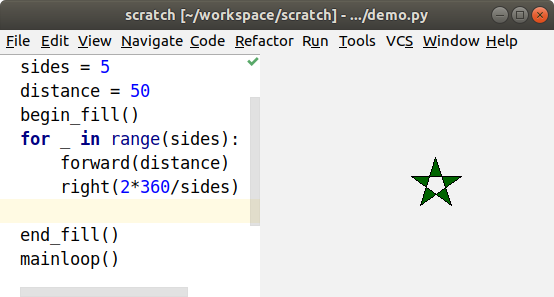

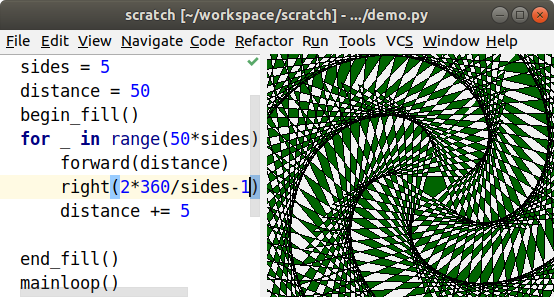

Another benefit to live coding like this is that I can be creative in a different way, by reacting to the results of my changes. How about an example? When I added the feature for filling polygons, I played with triangles, squares, and pentagons. Then I tried a star, and the middle wasn’t filled. After the surprise wore off, I realized that the centre is actually “outside” the polygon when you draw a star this way.

That gave me the idea to see how it would deal with a spiral, so I made the turtle go around the star five times, and made the sides longer and longer. That was cool, a striped star! Then I made it go around 50 times, and it filled the screen.

At this point, I wondered what would happen if I changed the angle, and the results blew my mind!

I didn’t set out to draw a pinwheel pattern and work out how to achieve that, I just stumbled across it while exploring how filled polygons work. When you combine live coding’s rapid response with an intuitive interface like turtle graphics, it’s easier to learn and create with. I think that was Bret Victor’s point in his Inventing on Principle video that inspired me to build this tool.

Live Coding Display

That was the fun learning tool, now what can you do with real code? I did create turtle classes that write to PDF or SVG, so that will let you use turtle graphics in a few more situations, but the main feature is a different view that helps you visualize what’s happening inside your code so you don’t have to keep running it in your head. I’ll start with a trivial chunk of code where I assign a variable, and then modify it.

s = 'Hello'

s += ', World!'

That’s easy to step through in your head and see that s is now

'Hello, World!' Remember, though, that I want to let your brain focus on

writing code instead of stepping through it.

From PyCharm’s Run menu, I choose Start Live Coding, and it opens the live coding display like the one on the right (below). The display shows me what’s in the variable after each change.

# Original source code | # Displays variables and loops

s = 'Hello' | s = 'Hello'

s += ', World!' | s = 'Hello, World!'

Let’s do something more interesting and write a library function that does binary search for a value in a sorted array. The live coding will show us what’s happening in our code so we don’t have to hold it all in our heads.

def search(n, a):

return -1

It’s a bad search function that never finds anything, but let’s see how it works when we call it.

def search(n, a): | n = 2 | a = [1, 2, 4]

return -1 | return -1

|

i = search(2, [1, 2, 4]) | i = -1

You can see the input parameters at the start of the function, and the return value at the end.

We’ll start looking for the value in the array, and the first place to look is the middle item.

def search(n, a): | n = 2 | a = [1, 2, 4]

low = 0 | low = 0

high = len(a) - 1 | high = 2

mid = low + high // 2 | mid = 1

if n == a[mid]: |

return mid | return 1

return -1 |

|

i = search(2, [1, 2, 4]) | i = 1

That was lucky! It was in the first place we looked, and you can see the

calculations as it goes. You see an abstract formula in the code, like

high = len(a) - 1, and you see the concrete result in the live coding

display, like high = 2. However, a search function usually won’t find the

item we’re searching for on the first try. Let’s ask for an item earlier in the

list and use a while loop to find it.

def search(n, a): | n = 1 | a = [1, 2, 4]

low = 0 | low = 0

high = len(a) - 1 | high = 2

while True: | |

mid = low + high // 2 | mid = 1 | mid = 0

v = a[mid] | v = 2 | v = 1

if n == v: | |

return mid | | return 0

if n < v: | |

high = mid - 1 | high = 0 |

return -1 |

|

i = search(1, [1, 2, 4]) | i = 0

The loop runs twice, and each run adds a column to the display showing the calculations. That’s a good example of how this tool differs from a debugger. With a debugger, you’re always looking at a single moment in time. Here, you can see the whole history of the search laid out on the screen, and you move back and forth through time just by moving your eye. It’s a lot like the difference that makes static visualizations of sorting algorithms easier to follow than animated sorting algorithms.

Now let’s look for an item later in the list.

def search(n, a): | n = 4 | a = [1, 2, 4]

low = 0 | low = 0

high = len(a) - 1 | high = 2

while True: | |

mid = low + high // 2 | mid = 1 | mid = 3

v = a[mid] | v = 2 | IndexError: list index out of range

if n == v: | |

return mid | |

if n < v: | |

high = mid - 1 | |

else: | |

low = mid + 1 | low = 2 |

return -1 |

|

i = search(4, [1, 2, 4]) | IndexError: list index out of range

Oops, I get an IndexError. Without the live coding display, I would just get a

traceback that shows where the error happened, but not how it happened. Now, I

can walk back from the error to see where things went wrong. mid is the index

value, and it’s calculated at the top of the loop. The two values that go into

it are both 2, so they should average to 2. Oh, I need parentheses to calculate

the average.

def search(n, a): | n = 4 | a = [1, 2, 4]

low = 0 | low = 0

high = len(a) - 1 | high = 2

while True: | |

mid = (low + high) // 2 | mid = 1 | mid = 2

v = a[mid] | v = 2 | v = 4

if n == v: | |

return mid | | return 2

if n < v: | |

high = mid - 1 | |

else: | |

low = mid + 1 | low = 2 |

return -1 |

|

i = search(4, [1, 2, 4]) | i = 2

What happens if we try to find a value that’s not in the list?

def search(n, a): | n = 3 | a = [1, 2, 4]

low = 0 | low = 0

high = len(a) - 1 | high = 2

while True: | | | | |

mid = (low + high) // 2 | mid = 1 | mid = 2 | mid = 1 | mid = 1 |

v = a[mid] | v = 2 | v = 4 | v = 2 | v = 2 |

if n == v: | | | | |

return mid | | | | |

if n < v: | | | | |

high = mid - 1 | | high = 1 | | |

else: | | | | |

low = mid + 1 | low = 2 | | low = 2 | low = 2 |

return -1 |

|

i = search(3, [1, 2, 4]) | RuntimeError: live coding message limit exceeded

I guess that while True wasn’t such a good idea, we’re stuck in an infinite loop. If you want to see some of the later loop runs, you can scroll over to the right.

From the third run on, the values in the loop don’t change, so we probably want to exit from the second or third run. If you look at the end of the second run, you can see that high is lower than low. That means that we’ve searched all the way from both ends to meet in the middle, and it’s time to give up.

def search(n, a): | n = 3 | a = [1, 2, 4]

low = 0 | low = 0

high = len(a) - 1 | high = 2

while low <= high: | |

mid = (low + high) // 2 | mid = 1 | mid = 2

v = a[mid] | v = 2 | v = 4

if n == v: | |

return mid | |

if n < v: | |

high = mid - 1 | | high = 1

else: | |

low = mid + 1 | low = 2 |

return -1 | return -1

|

i = search(3, [1, 2, 4]) | i = -1

At this point, I think I’m done. I can add a few entries and search for them to make sure everything is working. Also, if this were a real library module, I wouldn’t want to execute a call at the end of the file, so I only do it when I’m in live coding mode.

if __name__ == '__live_coding__':

i = search(3, [1, 2, 4])

Live Unit Tests

In that example, I kept changing the parameters to search for different items in the list. Wouldn’t each set of search parameters make a nice unit test? I think unit tests help you write better code, so you can use the live coding display as you add each unit test and make it pass.

In this section, I’ll write a function that counts the number of unique words in a list. However, words with the same letters are counted as the same word. For example, the words “apple”, “lemon”, and “melon” would only count as two words, because “lemon” and “melon” have the same letters in different order.

To start, I write a simple unit test that doesn’t have any duplicates.

from unittest import TestCase

from anagrams import count_anagrams

class AnagramsTest(TestCase):

def test_words(self):

words = ['apple', 'melon']

n = count_anagrams(words)

self.assertEqual(2, n)

I can run that in PyCharm by pressing

Ctrl+Shift+F10. Of course, that fails when I

run it as a unit test, because I haven’t written the count_anagrams() method.

I start by creating anagrams.py with a stupid version that always returns

zero.

def count_anagrams(words):

return 0

The test now fails with a reasonable complaint.

test_word_counter.py::AnagramsTest::test_words FAILED [100%]

0 != 2

Expected :2

Actual :0

<Click to see difference>

I want to see what’s happening as I make the unit test pass, so I open

anagrams.py, and then from the Run menu, choose Start Live Coding.

| ---------------- |

| SystemExit: True |

| ---------------- |

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['apple', 'melon']

return 0 | return 0

Now I can see the input parameters and the return value, as well as the fact that the test failed. Next, I make that test pass with the simplest code that could possibly work.

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['apple', 'melon']

return len(words) | return 2

Once the test passes, I can add another test method with another scenario. This one includes two copies of ‘melon’, so the number of unique words is still two.

def test_duplicate_words(self):

words = ['apple', 'melon', 'melon']

n = count_anagrams(words)

self.assertEqual(2, n)

I could make the test pass now, but it’s a little confusing when both tests are being displayed.

| ---------------- |

| SystemExit: True |

| ---------------- |

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['apple', 'melon', 'melon'] | words = ['apple', 'melon']

return len(words) | return 3 | return 2

Instead, I’ll convince PyCharm to only run the new test method. That becomes

even more useful as we add more and more test methods. Open the test file, click

somewhere in the new test method, and press

Ctrl+Shift+F10. That creates a new run

configuration that only runs the current test method. Open the anagrams.py

file, and from the Run menu, choose Start Live Coding again. Now

you can see the failing test on its own.

Each time you add a new test, create a new run configuration to run it. It’s

even easier if you start by calling each new test test(), and then rename it

once it passes. Then you can just leave the run configuration the same as you add

each new test.

| ---------------- |

| SystemExit: True |

| ---------------- |

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['apple', 'melon', 'melon']

return len(words) | return 3

To remove duplicates, just put all the words into a set before counting.

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['apple', 'melon', 'melon']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'apple' | word = 'melon' | word = 'melon'

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'apple'} | anagrams = {'apple', 'melon'} |

return len(anagrams) | return 2

When you get to the second copy of ‘melon’, the set doesn’t change.

Now we get to the interesting part: detecting anagrams.

def test_anagrams(self):

words = ['apple', 'melon', 'lemon']

n = count_anagrams(words)

self.assertEqual(2, n)

One way is to sort the letters in each word.

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['apple', 'melon', 'lemon']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'apple' | word = 'melon' | word = 'lemon'

word = ''.join( | word = 'aelpp' | word = 'elmno' | word = 'elmno'

sorted(word)) | | |

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'aelpp'} | anagrams = {'elmno', 'aelpp'} |

return len(anagrams) | return 2

You can see that the second and third iteration of the loop convert

‘melon’ and ‘lemon’ to ‘elmno’, and the set of anagrams doesn’t

change in the third iteration.

The next feature I want to add is to treat upper case and lower case the same, so I add a new test case.

def test_upper(self):

words = ['Melon', 'Lemon']

n = count_anagrams(words)

self.assertEqual(1, n)

Of course, it doesn’t pass.

| ---------------- |

| SystemExit: True |

| ---------------- |

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['Melon', 'Lemon']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'Melon' | word = 'Lemon'

word = ''.join( | word = 'Melno' | word = 'Lemno'

sorted(word)) | |

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'Melno'} | anagrams = {'Lemno', 'Melno'}

return len(anagrams) | return 2

You can see that ‘Melon’ and ‘Lemon’ get sorted into ‘Melno’ and ‘Lemno’, because upper-case letters sort before lower-case letters. We can fix that by switching all the words to lower case.

| ---------------- |

| SystemExit: True |

| ---------------- |

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['Melon', 'Lemon']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'Melon' | word = 'Lemon'

word = ''.join( | word = 'Melno' | word = 'Lemno'

sorted(word)) | |

word = word.lower() | word = 'melno' | word = 'lemno'

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'melno'} | anagrams = {'melno', 'lemno'}

return len(anagrams) | return 2

Oops, ‘Melon’ and ‘Lemon’ now get sorted into ‘melno’ and ‘lemno’. We fixed the case, but not the sort order. Switching to lower case before sorting the letters will fix it.

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['Melon', 'Lemon']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'Melon' | word = 'Lemon'

word = word.lower() | word = 'melon' | word = 'lemon'

word = ''.join( | word = 'elmno' | word = 'elmno'

sorted(word)) | |

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'elmno'} |

return len(anagrams) | return 1

Finally, I want to handle foreign words correctly. For example, the German word for street can be written either as ‘Straße’ or ‘Strasse’. Python knows how to convert from one to the other, so I’ll add another test case.

def test_case_folding(self):

words = ['Straße', 'Strasse']

n = count_anagrams(words)

self.assertEqual(1, n)

When I run the new test case, the words are counted separately.

| ---------------- |

| SystemExit: True |

| ---------------- |

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['Straße', 'Strasse']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'Straße' | word = 'Strasse'

word = word.lower() | word = 'straße' | word = 'strasse'

word = ''.join( | word = 'aerstß' | word = 'aerssst'

sorted(word)) | |

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'aerstß'} | anagrams = {'aerssst', 'aerstß'}

return len(anagrams) | return 2

To fix it, I just switch lower() to casefold().

def count_anagrams(words): | words = ['Straße', 'Strasse']

anagrams = set() | anagrams = set()

for word in words: | word = 'Straße' | word = 'Strasse'

word = word.casefold() | word = 'strasse' | word = 'strasse'

word = ''.join( | word = 'aerssst' | word = 'aerssst'

sorted(word)) | |

anagrams.add(word) | anagrams = {'aerssst'} |

return len(anagrams) | return 1

You can see that casefold() converts ‘ß’ to ‘ss’, while still

converting ‘S’ to ‘s’, and the test passes.

Now that I’ve made each test pass, I run the full test suite again to make sure I didn’t break any of the other tests. The easiest way to run it is to go to the top of the test file, and type Ctrl+Shift+F10.

Ran 5 tests in 0.002s

OK

It looks good, so I can publish my new library.

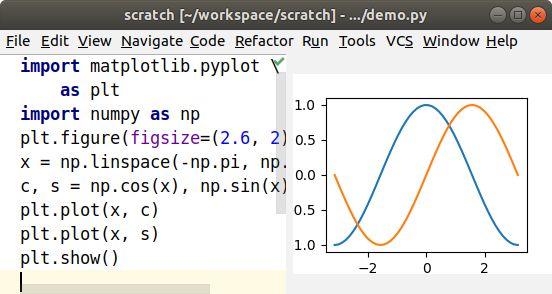

Matplotlib Preview

The Matplotlib graphing library has a lot of features, and it can be easier to fiddle with the settings if you have a preview that updates as you change them. I can see a preview by typing the following code, and then choosing Start Live Turtle from the Run menu.

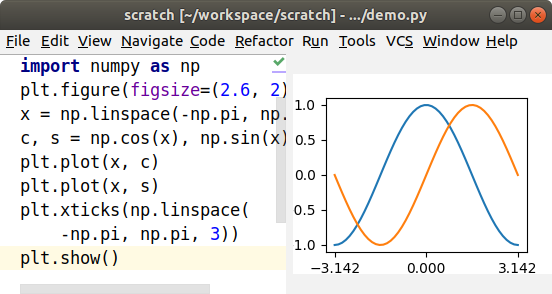

If I decide that I’d rather put the tick marks at π and -π, I can add a

call to plt.xticks(), and the preview immediately updates.

There are lots of Matplotlib tutorials around, and this preview can be useful for following along with a tutorial.

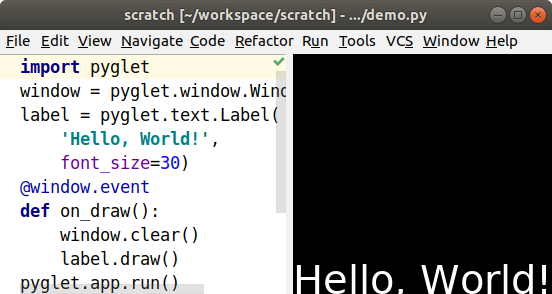

Pyglet Preview

Pyglet is a library for building user interfaces, and I can preview the user interface in the Live Turtle view.

See the Pyglet documentation for details on how to build an interface.

Learn More

There are some extra features available if you install the space tracer library. Remember, you can find installation instructions and descriptions of all the other Live Coding in Python plugins and tools by visiting donkirkby.github.io. Help me test it, and report your bugs. I’d also love to hear about any other projects working on the same kind of tools.